FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

First Vision | Alleged Contradictions

Summary: Critics have routinely asserted that Joseph Smith's account of the First Vision contain contradictions. This page gathers all the alleged "contradictions" and clarifies each, showing that Joseph Smith's accounts can easily be harmonized. Critics have challenged the First Vision on other grounds. They argue that there are embellishments and that there are historical anachronisms in the accounts. If you do not find what you're looking for on this page, be sure to visit those two pages that address embellishments or historical anachronisms.

Joseph Smith wrote several accounts of the First Vision. In his earliest written account from 1832, he speaks clearly about seeing “the Lord.” In later accounts, especially those from 1835 and 1838, he says that he saw two personages—God the Father and Jesus Christ. Some people claim this means Joseph changed his story. A closer look shows there are good reasons for the difference.

Even though Joseph does not clearly describe God the Father appearing in the 1832 account, he still refers to Him. At the start of the history, Joseph says that the First Vision was when he was “receiving the testimony from on high.” In Joseph’s later accounts, that “testimony” is when God the Father introduces Jesus Christ and tells Joseph who He is.

In the Bible and other scripture, a voice that comes “from heaven” or “from on high” usually means God the Father. Joseph used this same kind of language both before and after 1832. Because of this, many scholars believe Joseph understood the voice “from on high” to be the Father, even if he did not describe seeing Him clearly in that part of the story.

There is also a line in the 1832 account that says, “the Lord opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord.” Some readers think this could mean two beings—one who opens the heavens and another who appears.

Joseph’s way of writing in 1832 matches how visions are described in the Bible and the Book of Mormon. In the Book of Mormon, Lehi sees God on His throne, but Jesus Christ is the one who comes down and speaks to him. In the New Testament, the Apostle Paul describes seeing Jesus Christ in a vision, but he does not say he saw God the Father.

Joseph appears to have modeled part of his 1832 account after Paul’s experience. Since Paul focused on Christ and not the Father, Joseph may have done the same in his first written telling.

In the 1832 account, the main message is that Joseph’s sins were forgiven. In later accounts, Jesus Christ is the one who delivers that message after the Father introduces Him. This suggests that Joseph focused on Jesus in 1832 because Jesus was the one speaking to him and forgiving his sins. The account is centered on what mattered most to Joseph at that moment.

Joseph wrote the 1832 account himself, and it was the first time he tried to write his life story. Later accounts were mostly spoken and written down by others. Joseph once said that writing felt limiting and difficult for him. Because of this, the 1832 account is shorter and less detailed. As time went on, Joseph became better at explaining what happened and used clearer language.

Three of Joseph’s four main accounts clearly say that two personages appeared. The 1832 account can still be read in a way that fits with the others. The differences mostly come from what Joseph chose to emphasize, not from changing what he experienced.

Critics sometimes argue that Joseph Smith contradicted himself by saying that a “pillar of fire” appeared in some accounts of the First Vision and a “pillar of light” in others. A closer look at scripture, language, and Joseph’s own explanations shows that this difference is not a real contradiction.

First, in the Bible and other scriptures, fire and light are often used to describe the same divine presence. God appears to Moses in a burning bush that gives light but does not burn the bush (Exodus 3). The Lord leads Israel with a pillar of fire by night and a cloud by day (Exodus 13:21), showing that fire can function as a source of light. Heavenly beings are also described as shining, glowing, or appearing “like fire.” Because of this, describing a divine manifestation as either “fire” or “light” fits well within biblical language.

Second, Joseph’s own descriptions connect fire and light, rather than treating them as opposites. In the 1832 account, he says he saw a “pillar of fire, light above the brightness of the sun at noon day.” This wording already blends the two ideas. Joseph appears to be using familiar biblical imagery to describe something intensely bright and powerful, not trying to give a scientific description of its physical makeup.

Third, different words can describe the same experience, especially when someone is trying to put an extraordinary event into ordinary language. A blazing light can look like fire. Fire itself gives off light. When Joseph told or wrote about his experience in different settings and for different audiences, he used different words that pointed to the same reality—a brilliant, heavenly manifestation coming from God.

Fourth, Joseph’s later accounts aim for clarity, not correction. As he retold the story over time, he often chose words that would help listeners better understand what he saw. “Light” may have been clearer and less confusing than “fire” for later audiences, especially since the pillar did not burn anything. This is the same way people today might describe the same event differently depending on context, without contradicting themselves.

In short, the use of “pillar of fire” in one account and “pillar of light” in another reflects biblical style, natural language variation, and growing clarity, not a contradiction. Both expressions describe the same overwhelming divine glory and are completely consistent with each other and with scripture.

Critics have occasionally asserted that early Latter-day Saint sources understood Joseph Smith’s First Vision to involve only an angel rather than God the Father and Jesus Christ. This claim is based on selective quotations from early leaders, secondary retellings, and the use of the term angel in some historical contexts. Joseph Smith’s own early accounts also contribute to the confusion. In his 1835 journal, Joseph referred to his youthful experiences as involving the “first visitation of angels” and stated that “many angels” were present. Importantly, the same account also explicitly describes the appearance of two personages, one of whom testified that Jesus Christ was the Son of God. A careful examination of the primary sources, however, shows that these references do not reflect a doctrinal misunderstanding of the First Vision, but instead arise from differences in terminology, abbreviated retellings, and occasional conflation of distinct visionary events.

Oliver Cowdery wrote an early history of Joseph Smith in 1834–1835 for a Church newspaper called the Messenger and Advocate. Critics often point to this account to claim that Cowdery believed Joseph Smith saw only an angel and not God the Father and Jesus Christ in the First Vision. A closer and simpler reading of Cowdery’s writing shows that this conclusion goes beyond what Cowdery actually said.

In his account, Cowdery explained that Joseph Smith was confused by the many churches around him and wanted to know whether God really existed. Joseph prayed, and an angel appeared and told him that his sins were forgiven. Cowdery then moved directly into a story that closely matches later accounts of the angel Moroni and the gold plates. Because Cowdery did not clearly separate these events, some readers assume he believed there was only one vision.

However, Cowdery’s goal was not to give a detailed timeline of every vision Joseph experienced. He was writing a brief introduction to Joseph Smith’s calling as a prophet for readers who already believed Joseph was inspired by God. To keep the story simple, Cowdery combined Joseph’s early spiritual experiences into one shortened account focused on forgiveness and calling.

Cowdery even corrected himself in a later issue after realizing he had listed the wrong age for Joseph. This shows that the history was informal and not meant to be a carefully edited record. At no point did Cowdery say that Joseph had only one vision, nor did he deny later accounts that describe God the Father and Jesus Christ appearing to Joseph.

Cowdery’s writing also fits well with Joseph Smith’s own 1832 account, which focused more on Joseph seeking forgiveness than on explaining exactly who appeared to him. At the time, people often used the word angel in a general way to describe messages from heaven.

There is no evidence that Oliver Cowdery rejected or misunderstood the First Vision. His use of the word angel reflects a short, simplified retelling of Joseph Smith’s early experiences, not a different belief about what Joseph actually saw.

Critics sometimes claim that Brigham Young believed Joseph Smith saw only an angel and not God the Father and Jesus Christ. This claim is usually based on a short quotation taken from one of Young’s sermons, where he said, “The Lord did not come… but He did send His angel.” When read by itself, this line can sound like Brigham Young was denying the First Vision as it is taught today. However, reading the full sermon shows that this interpretation is incorrect:

The Lord did not come with the armies of heaven, in power and great glory, nor send His messengers panoplied with aught else than the truth of heaven, to communicate to the meek the lowly, the youth of humble origin, the sincere enquirer after the knowledge of God. But He did send His angel to this same obscure person, Joseph Smith Jun., who afterwards became a Prophet, Seer, and Revelator, and informed him that he should not join any of the religious sects of the day, for they were all wrong; that they were following the precepts of men instead of the Lord Jesus; that He had a work for him to perform, inasmuch as he should prove faithful before Him. (Journal of Discourses 2:170-171)

In the full statement, Brigham Young was not saying that the Lord never came to Joseph Smith. Instead, he was explaining how the Lord chose to reveal Himself. Young specifically said that the Lord did not come “with the armies of heaven, in power and great glory.” In other words, God did not appear with overwhelming display, grandeur, or force. Instead, He worked through humble means that matched Joseph Smith’s situation and character.

Brigham Young then explained that the Lord “did send His angel” to Joseph Smith. Importantly, the sentence continues by saying that the Lord informed Joseph that he should not join any of the religious sects because they were all wrong. Grammatically and logically, Brigham Young is describing the angel as the messenger, while the message itself comes from the Lord. This fits well with how divine communication is described throughout the Bible, where God often teaches or commands through angels.

It is also important to remember that Joseph Smith experienced multiple angelic visitations, especially from the angel Moroni. Brigham Young frequently spoke in broad, summarized language about Joseph’s early calling, often blending different events together to make a general point about divine authority rather than to give a detailed history lesson. His sermon was focused on showing that God chose a humble young man and guided him step by step, not on listing every vision in precise order.

There is strong evidence elsewhere that Brigham Young accepted Joseph Smith’s account of seeing God the Father and Jesus Christ. He taught openly that God the Father and the Son were separate beings and fully supported Joseph Smith’s prophetic testimony. The selective use of one sentence from a longer sermon does not reflect Young’s overall beliefs.

When read in full and in context, Brigham Young’s words do not show confusion or disagreement about the First Vision. Instead, they show his effort to explain that God did not appear with dramatic display, but worked through angels and personal revelation to call Joseph Smith in a quiet and humble way.

Some critics claim that Joseph Smith’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, said his First Vision was only of an angel — and not of God the Father and Jesus Christ. This idea usually comes from a letter she wrote in January 1831. However, when her words are read carefully and in context, it is clear that she was not trying to describe the First Vision itself, and she did not deny that Joseph saw God and Christ. Lucy’s letter was not written to explain every vision Joseph had. Instead, she wrote it to introduce the Book of Mormon to her siblings and explain how that book came forth. In that letter, she quoted language that closely matches a passage in the Church’s Articles and Covenants (Doctrine and Covenants 20:5–8) — language that refers to God ministering to Joseph by an angel who gave him commandments and assistance to translate the plates.

Critics sometimes point to this and say Lucy was referring to the First Vision. But her letter does not say that the visit of the angel was Joseph’s first spiritual experience, nor does it suggest that he only saw an angel instead of God the Father and Jesus Christ. Instead, her wording reflects the common devotional style and biblical language of the time — where an angel is described as a messenger of God who brings instruction or revelation.

In her letter, Lucy actually echoes Doctrine & Covenants 20, received in 1830, that already assumes the First Vision had taken place and that Joseph had received a mission from the Lord. The letter closely paraphrases that text.

Compare this with Mother Smith's letter:

"Joseph, after repenting of his sins and humbling himself before God, was visited by an holy angel whose countenance was as lightning and whose garments were white above all whiteness, who gave unto him commandments which inspired him from on high; and who gave unto him, by the means of which was before prepared, that he should translate this book."

Compare both of the above sources with the Prophet's 1832 First Vision narrative:

"I felt to mourn for my own sins....[The Lord said during the First Vision,] 'thy sins are forgiven thee'....after many days I fell into transgression and sinned in many things....I called again upon the Lord and he shewed unto me a heavenly vision for behold an angel of the Lord came and stood before me....the Lord had prepared spectacles for to read the Book therefore I commenced translating the characters."

Critics also fail to point out that almost exactly two months before Lucy Mack Smith wrote her letter, four Latter-day Saint missionaries (Oliver Cowdery, Orson Pratt, Peter Whitmer Jr. and Ziba Peterson) were publicly teaching that Joseph Smith had seen God "personally" and had received a commission from Him to preach true religion.[1] It is specifically stated in the newspaper article that records this information that the missionaries made their comments about 1 November 1830 - shortly after the Church was formally organized. Some critics who do acknowledge this newspaper article attempt to dismiss it by calling it a "vague" reference, despite the clear wording that the missionaries taught that Joseph "had seen God frequently and personally."[2]

Although one critic of the Church indicates that the letter was “unpublished until 1906”,[3] he does not indicate where, or by whom. First published by Ben E. Rich, President of the Southern States Mission, the letter has been long available to interested students of Latter-day Saint history.[4]

It should be noted that the Lucy Mack Smith letter was not even available for publication until just shortly before it appeared in print because it was in a descendant's possession. The introduction to the letter published in the Elders' Journal states: "The following very interesting and earnest gospel letter written by Lucy Mack Smith, mother of the Prophet Joseph, to her brother, Solomon Mack and his wife, was presented to President Joseph F. Smith a few weeks ago by Mrs. Candace Mack Barker, of Keene, N[ew] H[ampshire], a grand-daughter of Solomon Mack, to whom the letter is addressed. Mrs. Barker stated that it was her desire to place the letter in the hands of those who would appreciate its contents and preserve it as she felt it properly deserved."[5] The idea that Lucy Mack was trying to hide a First Vision story is not supported by the historical record.

In short, Lucy Mack Smith’s 1831 letter does not say that Joseph’s First Vision was of an angel instead of God and Christ. Instead, she was summarizing part of the early Church’s understanding of how revelation came to Joseph — in this case, through an angelic messenger connected with the coming forth of the Book of Mormon — and she did not intend to give a full history of every heavenly manifestation Joseph experienced.

Some critics point to a statement by John Taylor in an 1879 sermon where he referred to Joseph Smith asking an angel which church was right. They claim this shows that Taylor was confused about the First Vision. While the quotation itself is accurate, it does not show confusion when it is placed in its full historical setting.

“…just as it was when the prophet Joseph asked the angel which of the sects was right that he might join it. The answer was that none of them are right. What, none of them? No. we will not stop to argue that question; the angel merely told him to join none of them that none of them were right.” (Journal of Discourses vol. 20, p. 167)

John Taylor was deeply familiar with the First Vision account. In fact, he served as the editor of the Church’s newspaper, Times and Seasons, in 1842–1843. During that time, he oversaw the publication of Joseph Smith’s history, which included the clear account of the First Vision describing the appearance of God the Father and Jesus Christ. It is not reasonable to believe that Taylor could publish this material without understanding or accepting it.

Taylor also had direct involvement with the Pearl of Great Price. The First Vision account was included in the Pearl of Great Price when the Pearl of Great Price was first published in 1851, and John Taylor approved a new American edition in 1878—only one year before the sermon critics quote. This shows that he was well aware of the official First Vision narrative.

On October 7th, 1878, nearly a year and a half before his 1879 sermon, he wrote a letter in behalf of the Quorum of the Twelve commenting upon a book by Edward W. Tullidge entitled Life of Joseph Smith. In that letter, he wrote:

God the Father and Jesus, with the ancient apostles, prophets, patriarchs and men of God have revealed to Joseph Smith principles on which hang the destinies of the world

Even more telling is that on the same day as the 1879 sermon where Taylor used the word angel, he also spoke of the Father, the Son, and Moroni appearing to Joseph Smith:

When Jesus sent forth his servants formerly he sent them to preach this Gospel. When the Father and the Son and Moroni and others came to Joseph Smith, he had a priesthood conferred upon him which he conferred upon others for the purpose of manifesting the laws of life, the Gospel of the Son of God, by direct authority, that light and truth might be spread forth among all nations. (Journal of Discourses 20:257)

This shows that Taylor was not denying or forgetting the First Vision. Instead, he was speaking in a brief and informal way during part of his remarks and then referring more fully to Joseph’s experiences elsewhere.

So why did John Taylor use the word angel at all? The most likely explanation is that he was either speaking generally about divine messengers or using biblical language, where heavenly beings are sometimes called angels even when they act with God’s authority. In the Bible, for example, God Himself is sometimes called an “angel” because the word means messenger.

When all of John Taylor’s writings and sermons are considered together, it becomes clear that he fully understood and taught that Joseph Smith saw God the Father and Jesus Christ in the First Vision. The single reference to an angel does not reflect confusion, but rather a brief or symbolic use of language taken out of context.

Some critics claim that Orson Pratt believed Joseph Smith saw only an angel and not God the Father and Jesus Christ. This claim is usually based on a short quote from an 1869 sermon where Pratt said that “God had sent an angel” to Joseph Smith:

“By and by an obscure individual, a young man, rose up, and, in the midst of all Christendom, proclaimed the startling news that God had sent an angel to him;… This young man, some four years afterwards, was visited again by a holy angel.” (Journal of Discourses, Vol.13, pp.65-66)

When this short quote is read by itself, it can sound like Pratt misunderstood the First Vision. But reading the full sermon shows that this is not true. In the same sermon, Orson Pratt clearly explained what Joseph Smith said he saw.

By and by an obscure individual, a young man, rose up, and, in the midst of all Christendom, proclaimed the startling news that God had sent an angel to him; that through his faith, prayers, and sincere repentance he had beheld a supernatural vision, that he had seen a pillar of fire descend from Heaven, and saw two glorious personages clothed upon with this pillar of fire, whose countenance shone like the sun at noonday; that he heard one of these personages say, pointing to the other, ‘This is my beloved Son, hear ye him.’ This occurred before this young man was fifteen years of age; and it was a startling announcement to make in the midst of a generation so completely given up to the traditions of their fathers; and when this was proclaimed by this young, unlettered boy to the priests and the religious societies in the State of New York, they laughed him to scorn. ‘What!’ said they, “visions and revelations in our day! God speaking to men in our day!” They looked upon him as deluded; they pointed the finger of scorn at him and warned their congregations against him. ‘The canon of Scripture is closed up; no more communications are to be expected from Heaven. The ancients saw heavenly visions and personages; they heard the voice of the Lord; they were inspired by the Holy Ghost to receive revelations, but behold no such thing is to be given to man in our day, neither has there been for many generations past.’ This was the style of the remarks made by religionists forty years ago. This young man, some four years afterwards, was visited again by a holy angel. (Journal of Discourses, Vol.13, pp.65-66)

Pratt taught that Joseph saw a pillar of fire come down from heaven and that he saw two glorious personages inside that light. He described their faces shining like the sun and said that Joseph heard one of them speak while pointing to the other and saying, “This is my Beloved Son, hear ye him.” This is a clear and accurate description of the First Vision as Joseph Smith later recorded it.

Pratt’s use of the word angel at the beginning of the sermon does not replace or contradict this description. Instead, Pratt was summarizing Joseph’s message to the world in simple terms before explaining the details. In the 1800s, Church leaders often used the word angel to mean a messenger sent by God, especially when speaking to audiences who were unfamiliar with Latter-day Saint beliefs. At the end of the sermon, Pratt also spoke about Joseph Smith being visited “four years afterwards” by another angel. This clearly refers to the visit of the angel Moroni, showing that Pratt understood Joseph Smith had more than one heavenly experience and that these events were separate.

When the full sermon is read, it is clear that Orson Pratt knew and taught that Joseph Smith saw God the Father and Jesus Christ in the First Vision. The claim that Pratt was confused comes from quoting only a small part of his words and leaving out the section where he gives a detailed and correct explanation of the vision.

Wilford Woodruff is claimed to have said in an 1855 sermon that the Church had been established in the last days only by "the ministering of an holy angel", and not by the Father and the Son.[6] The following text is the one used by critics of the Church to try and make it look like Apostle Wilford Woodruff taught something other than the traditional storyline of the First Vision.

An examination of the original text of the sermon in question reveals that Wilford Woodruff's words are being taken out of context by critics. The bolded words below show which sections of the paragraph have been selected by detractors to try and rewrite history.

When critics break the above quotation into pieces in the manner that they have, they create an unrecognized problem for themselves. A careful reading of this material indicates that it was not the angel who told Joseph Smith that "the gospel was not among men"; it was the "the Lord" who provided this information (see the capitalized/italicized words above: ANGEL, THE LORD, HE, HIS). The anti-Mormons have, through their editing of the text, made it falsely appear as if the words of the angel and the Lord were one and the same. Woodruff's quote does not state that it was the angel who told Joseph Smith that "the gospel was not among men"; it was the "the Lord" who provided this information

The attempt to use Wilford Woodruff's words to obscure the details of Mormon history is a misguided one because the evidence does not lead to the conclusion that critics advocate. Elder Woodruff was in the second highest leadership quorum of the Church during the lifetime of Joseph Smith and never once did he mention that the Prophet told two different tales about the founding of the last gospel dispensation.

It is difficult to believe that Elder Wilford Woodruff did not have an accurate knowledge of the traditional First Vision story prior to his 1855 remarks since on 3 February 1842 he became the superintendent of the printing office in Nauvoo, Illinois where the Times and Seasons newspaper was published[8] and remained there through at least 8 November 1843.[9] These dates are significant because in-between them the Prophet Joseph Smith had two separate accounts of the First Vision printed on the pages of the Times and Seasons and so Elder Woodruff would have been the person who was ultimately responsible for their production and distribution.

It should also be noted that before Elder Woodruff made his 1855 remarks six other members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles published First Vision accounts: (Orson Pratt - 1840, 1850, 1851); (Orson Hyde - 1842); (John E. Page - 1844); (John Taylor - 1850); (Lorenzo Snow - 1850); (Franklin D. Richards - 1851, 1852). It seems highly unlikely that Elder Woodruff would have remained unaware of these publications, which were made available to the public by his closest associates.

Apostle George A. Smith said on two separate occasions that Joseph Smith's First Vision was of an "angel"—not of the Father and the Son. However, the argument that George A. Smith was simply not aware of a Father-and-Son First Vision account when he made his "angel" statements is nonsense since it can be shown from a documentary standpoint that he did indeed have prior knowledge of such a thing. An argument of ignorance is also untenable in light of the fact that Brother Smith's close associates in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had published orthodox recitals of the First Vision on nine different occasions long BEFORE he made his verbal missteps at the pulpit: (Orson Pratt - 1840, 1850, 1851); (Orson Hyde - 1842); (John E. Page - 1844); (John Taylor - 1850); (Lorenzo Snow - 1850); (Franklin D. Richards - 1851, 1852).

This does not mean that Brother Smith was not aware of the Father and the Son appearing to the Prophet at the time that he made his anomalous remarks. The following timeline demonstrates that the Prophet's cousin was well aware of the official version of events. His out-of-place comments need to be evaluated from that perspective.

The timeline shows that George A. Smith was accurate in relating First Vision details when he had a physical text to read from. The pattern that can be seen in the timeline above is that George A. Smith was accurate in relating First Vision details when he had a physical text to read from or was formally writing down historical matters; he was accurate on many points when he was talking extemporaneously; he corrected himself after delivering erroneous verbal remarks.

Orson Hyde said during a General Conference in 1854:"Some one may say, 'If this work of the last days be true, why did not the Saviour come himself to communicate this intelligence to the world?'" Was Orson Hyde unaware of the details of the Father and Son appearing to Joseph in the First Vision?

When Elder Orson Hyde was discoursing in General Conference on 6 April 1854 he was NOT speaking about the First Vision (a story he knew very well from previously published literature) - he was trying to teach the Latter-day Saints about "the grand harvest" which would take place during "the winding up scene" and the part that "angels" would have in it. The evidence suggests that Elder Hyde was utilizing section 110 of the Doctrine and Covenants as the basis for some of his remarks about angels, NOT about the events that took place within the Sacred Grove.

The proper context of Elder Hyde’s remarks can be determined simply by examining his opening statement. There he makes it clear that because it was currently the season for sowing crops he wanted to discourse on some parable imagery found in the 13th chapter of the New Testament book of Matthew (verses 1–9, 36–43).

Elder Hyde specifically mentioned that the "angels" were the agency through which "this reaping dispensation was committed to the children of men" and that these heavenly beings held "the keys of this dispensation." With these words he may well have been referring to the episode recorded in section 110 of the Doctrine and Covenants where angels tell Joseph Smith - "the keys of this dispensation are committed into your hands" (v. 16). They also "committed the gospel of the dispensation of Abraham" to the Prophet (v. 12) and, furthermore, they "committed unto [him] the keys of the gathering" (v. 11) - [harvest imagery]. Elder Hyde said in his sermon that the angels brought the news that "the time of the end was drawing nigh" and, significantly, the last of the angels to appear in D&C 110 said, "the great and dreadful day of the Lord is near, even at the doors" (v. 16).

A summary of Elder Hyde’s comments shows that he did not intend to speak about the First Vision at all; he wanted to impress upon that Saints that the latter-day work of gathering (the figurative harvest imagery) was inaugurated by angels and they would also play a role in the figurative separation of the wheat and the tares.

When Orson Hyde was in London, England on a mission he wrote to the Prophet Joseph Smith and informed him: “I have written a book to publish in the German language, setting forth our doctrine and principles in as clear and concise a manner as I possibly could. After giving the history of the rise of the Church, in something the manner that Br[other] O[rson] Pratt did, I have written a snug little article upon every point of doctrine believed by the Saints.”[17]

It is high unlikely that Elder Hyde did not possess an accurate understanding of the First Vision story before the year 1854.

Critics quote a portion of a sermon delivered at the Salt Lake Tabernacle on November 8, 1857 by Heber C. Kimball, in which it appears that he denies that God and Jesus appeared to Joseph Smith. Here is what the critics quote:

Do you suppose that God in person called upon Joseph Smith, our Prophet? God called upon him; but God did not come himself and call, but he sent Peter to do it. Do you not see? He sent Peter and sent Moroni to Joseph, and told him that he had got the plates. Did God come himself? No; he sent Moroni and told him there was a record,…Well, then Peter comes along. Why did not God come? He sent Peter, do you not see? Why did he not come along? Because he has agents to attend to his business, and he sits upon his throne and is established at head-quarters, and tells this man, ‘Go and do this;’ and it is behind the vail just as it is here. You have got to learn that.

The very same evidence that was used in the construction of the anti-Mormon charge about Heber C. Kimball can be used to topple it. Kimball's remarks about God not appearing cannot be legitimately applied to Joseph Smith's First Vision experience. This argument is a classic example of taking an isolated statement out of its proper context and drawing a false conclusion based upon faulty evidence. When the entire sermon of Heber C. Kimball is examined in detail, the anti-Mormon argument quickly falls apart. Here is the full quote:

If God confers gifts, and blessings, and promises, and glories, and immortality, and eternal lives, and you receive them and treasure them up, then our Father and our God has joy in that man. . . . Do you not see [that] God is not pleased with any man except those that receive the gifts, and treasure them up, and practice upon those gifts? And He gives those gifts, and confers them upon you, and will have us to practice upon them. Now, these principles to me are plain and simple.

Do you suppose that God in person called upon Joseph Smith, our Prophet? God called upon him; but God did not come Himself and call, but He sent Peter to do it. Do you not see? He sent Peter and sent Moroni to Joseph, and told him that he had got the plates. Did God come Himself? No: He sent Moroni and told him there was a record, and says he, "That record is [a] matter that pertains to the Lamanites, and it tells when their fathers came out of Jerusalem, and how they came, and all about it; and, says he, "If you will do as I tell you, I will confer a gift upon you." Well, he conferred it upon him, because Joseph said he would do as he told him. "I want you to go to work and take the Urim and Thummim, and translate this book, and have it published, that this nation may read it." Do you not see, by Joseph receiving the gift that was conferred upon him, you and I have that record?

Well, when this took place, Peter came along to him and gave power and authority, and, says he, "You go and baptize Oliver Cowdery, and then ordain him a priest." He did it, and do you not see his works were in exercise? Then Oliver, having authority, baptized Joseph and ordained him a priest. Do you not see the works, how they manifest themselves?

Well, then Peter comes along. Why did not God come? He sent Peter, do you not see? Why did He not come along? Because He has agents to attend to His business, and He sits upon His throne and is established at headquarters, and tells this man, 'Go and do this'; and it is behind the veil just as it is here."[19]

From a careful reading of this text it can be concluded that Kimball was talking about (#1) the appearance of the angel Moroni in 1823 in connection with the coming forth of the Book of Mormon and (#2) the appearance of the apostle Peter in 1829 in connection with the bestowal of the Melchizedek Priesthood. He was talking about two heavenly beings bestowing "gifts" upon Joseph Smith on two different occasions; he was saying that in these two instances God sent His agents to accomplish particular works. However, Heber C. Kimball said absolutely nothing in this statement about the First Vision which occurred in 1820.

It cannot be successfully argued that Heber C. Kimball was not aware of the First Vision story by this point in time either, since no less a person than President Brigham Young recorded in his journal that Brother Kimball was present with several other General Authorities about two and a half months earlier (13 August 1857) when they placed a copy of the Pearl of Great Price inside the southeast cornerstone of the Salt Lake Temple.[20] This volume contained the 1838 account of the First Vision which was published by the Prophet Joseph Smith in Nauvoo, Illinois in 1842. There were also several other publications placed inside the temple cornerstone which rehearsed the First Vision story. These included:

When Latter-day Saints describe Joseph Smith’s First Vision, they commonly note that he was very young at the time—about fourteen years old. This understanding comes primarily from Joseph’s later, more formal accounts, but it is also supported by his earliest writings when those documents are read in their historical context.

The most familiar account of the First Vision is Joseph Smith’s 1838–39 history, now canonized as Joseph Smith–History in the Pearl of Great Price. In that narrative, Joseph explained that the vision occurred in the spring of 1820, when he was “an obscure boy, only between fourteen and fifteen years of age.” Since Joseph was born on December 23, 1805, he would have been 14 years old during the spring of 1820, turning fifteen later that year.

Joseph’s other firsthand retellings of the First Vision are consistent with this timeline. In his 1835 account, he said the experience happened when he was “about 14 years old.” In an 1842 summary prepared for publication, he likewise stated that he was “about fourteen years of age” when the event took place. Even in casual recollections to acquaintances, Joseph repeatedly described the First Vision as something that happened in his early teens.

The main question arises from Joseph’s earliest known account, written in 1832. In this document, Joseph (or his scribe) stated that the vision occurred while he was “in the sixteenth year of my age.” At first glance, some readers assume this must mean Joseph was fifteen or even sixteen years old, creating a potential conflict with his later accounts. However, this phrase requires careful historical interpretation.

In early nineteenth-century English usage, saying someone was “in their sixteenth year” did not mean they were sixteen years old. Rather, it meant they had begun the year leading toward their sixteenth birthday. In other words, a person entered their “sixteenth year” immediately after turning fifteen, just as an infant is said to be “in their first year” from birth, not at age one. This older way of reckoning age was common in Joseph Smith’s day and appears in other contemporary documents.

Additionally, the phrase in the 1832 manuscript appears to have been inserted between the lines, suggesting it may reflect later clarification rather than careful chronological precision. The 1832 account itself was not intended as a polished autobiography; instead, it was a private, spiritual narrative focused on Joseph’s sins, repentance, and forgiveness, not on exact dates.

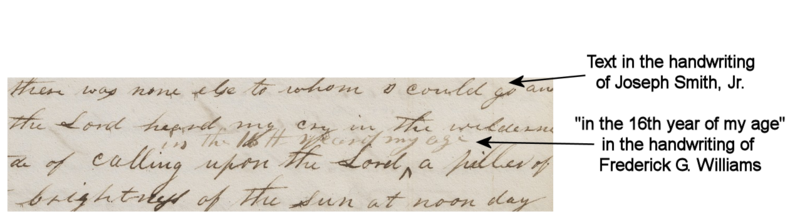

In the 1832 account, Frederick G. Williams inserted the "in the 16th year of my age" above Joseph's text after Joseph had already written it. (See: "History, circa Summer 1832," The Joseph Smith Papers)

When Joseph’s accounts are considered together, they present a coherent picture. He consistently placed the First Vision in the spring of 1820 and consistently described himself as about fourteen years old at the time. The wording in the 1832 account fits comfortably within this framework once historical language and age-counting conventions are taken into account.

In short, the documentary evidence supports the traditional understanding: Joseph Smith was fourteen years old when he experienced the First Vision, a young teenager seeking divine guidance in a time of religious confusion.

The multiple accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision have long attracted both devotion and criticism. Among the most common objections is the claim that Joseph changed his stated reason for praying over time. Critics argue that his earliest account (1832) presents a desire for forgiveness of sins as his primary motivation, while later accounts—especially the 1838 narrative canonized in the Pearl of Great Price—emphasize a desire to know which church was true. According to this view, the differing emphases represent a contradiction and suggest that the First Vision story evolved over time.

A close reading of all the available evidence, however, shows that this conclusion rests on an oversimplified comparison of selective phrases rather than on the full substance of the documents. When the accounts are read carefully and in their historical and religious context, Joseph Smith’s motivations appear consistent rather than contradictory. From the beginning, he expressed two closely related concerns: a desire to be forgiven of sins and a desire to worship God correctly by affiliating with the true church.

Critics typically contrast two statements:

From these statements alone, critics conclude that Joseph originally prayed only for forgiveness and later revised his story to include questions about church authority. This comparison, however, strips both texts of their surrounding explanations and ignores the broader religious assumptions of Joseph Smith’s world.

The 1832 account, partly written in Joseph Smith’s own hand, devotes significant space to describing the spiritual journey that led him to prayer. Far from portraying a narrow concern with personal guilt alone, the account reveals a young man grappling with multiple, interconnected questions.

Between the ages of twelve and fifteen, Joseph became deeply concerned about “the welfare of [his] immortal soul.” His search of the scriptures led him to compare biblical Christianity with the behavior and teachings of the denominations around him. This comparison caused him to “marvel exceedingly” and grieve that those who professed religion did not live in a manner consistent with scripture. Joseph further concluded—based on both scripture study and personal observation—that “there was no society or denomination that built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ as recorded in the New Testament.” He mourned not only for his own sins, but also “for the sins of the world,” reflecting concern for widespread religious corruption, not merely individual failure.

Only after recounting all of these considerations does Joseph explain why he prayed: “When I considered all these things… therefore I cried unto the Lord for mercy.” His prayer was a response to the cumulative weight of doctrinal confusion, perceived apostasy, concern for correct worship, and personal conviction of sin.

In other words, forgiveness of sins was not the sole motivation for prayer—it was part of a broader religious crisis.

Understanding Joseph Smith’s motivations requires recognizing an important feature of early nineteenth-century American Christianity. As historian Christopher C. Jones has observed, Joseph’s accounts strongly resemble Methodist conversion narratives, in which forgiveness of sins and correct church affiliation were inseparable. In Joseph’s religious culture, one found forgiveness by joining the right church and adhering to correct doctrine.[21]

Under this framework, asking God for forgiveness inherently involved asking God which church—and which teachings—were correct. The two concerns rode in tandem, not in competition. Thus, even if the 1832 account emphasizes repentance language, it does not exclude institutional or doctrinal concerns. On the contrary, the account explicitly laments the failure of existing denominations to embody New Testament Christianity.

Significantly, in the vision itself, Joseph is told not merely that his sins are forgiven, but that “the world lieth in sin” and that religious leaders “draw near to me with their lips while their hearts are far from me,” echoing Matthew 15:8–9. This language points beyond personal forgiveness toward a general apostasy and the need for divine restoration.

The 1832 account also draws on scriptural language that Joseph later revisited during his translation of the Bible—particularly in JST Psalm 14. That psalm laments the loss of truth in the last days, declaring that “none doeth good” because religious teachers have gone astray. Scholars such as Joseph Fielding McConkie, Matthew Brown, Don Bradley, and Walker Wright have noted that Joseph’s JST rendering of Psalm 14 closely parallels themes in the First Vision and may even have influenced the language of his early history.[22]

These parallels reinforce the idea that Joseph’s concern was not simply moral failure among individuals, but doctrinal corruption among religious teachers and institutions. Under this reading, the 1832 account implicitly addresses the same “which church is true?” question that later accounts state more explicitly.

Joseph Smith’s later narrations of the First Vision vary in detail depending on audience and purpose. The 1835 account includes both concerns explicitly: uncertainty about which religious system was right and the declaration that his sins were forgiven. The 1838 account foregrounds religious confusion and the question of church authority but still alludes to “many other things” said during the vision that are not recorded—leaving room for experiences, such as forgiveness, described elsewhere.

Similarly, third-party retellings by Orson Pratt (1840) and Orson Hyde (1842) combine both themes: preparation for a future state, concern for salvation, confusion among denominations, and assurance of divine favor.

Rather than showing a shift in motivation, these accounts show selective emphasis, shaped by context and audience. None of them deny either concern; each highlights different aspects of the same religious struggle.

The claim that Joseph Smith changed his motivation for seeking revelation does not survive careful scrutiny. Across all accounts, Joseph presents himself as a young man profoundly concerned with salvation—how to prepare for eternity, how to worship God correctly, and how to receive forgiveness of sins. In his worldview, these were not separate questions but variations on the same theme. Differences among the First Vision accounts reflect changes in emphasis, audience, and narrative purpose—not contradiction. When read in context and within the religious culture of Joseph Smith’s time, the accounts form a coherent and internally consistent explanation of why he went to the grove to pray in 1820.

Rather than depicting an evolving fabrication, the evidence shows a stable core story: Joseph Smith sought divine guidance because he believed his soul—and the religious world around him—were in need of correction that only God could provide.

A frequently repeated claim in critical discussions of early Latter-day Saint history is that Oliver Cowdery taught that Joseph Smith did not even know whether a “Supreme Being” existed prior to 1823, thereby implying ignorance of God before the visit of the angel Moroni. This claim is based on a selective and decontextualized reading of Oliver Cowdery’s Church history, published in installments in the Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate beginning in late 1834. When read carefully and in full historical context, Oliver’s account does not deny Joseph Smith’s First Vision, nor does it suggest that Joseph was an atheist prior to Moroni’s visit. Instead, it reflects a complex narrative strategy, one that presupposes Joseph’s earlier divine encounter while choosing not to narrate it directly.

In December 1834, Oliver Cowdery began publishing a formal history of the Church in the Messenger and Advocate. In the first installment, Oliver accurately placed Joseph Smith at fourteen years of age during a period of intense religious excitement and revivalism. He described the surrounding sectarian contention and Joseph’s deep concern for his soul—an account that clearly parallels Joseph Smith’s own descriptions of the circumstances leading to the First Vision.

This initial installment builds narrative momentum toward a revelatory experience. Readers naturally expect the culminating event to be Joseph’s First Vision. However, in the second installment, published in February 1835, Oliver takes an unexpected turn.

In the February 1835 installment, Oliver abruptly “corrects” Joseph’s age from fourteen to seventeen and proceeds to describe the visit of the angel Moroni rather than the First Vision. He does not narrate the vision of the Father and the Son explicitly, creating the impression—at least for modern readers unfamiliar with the broader documentary record—that Oliver either did not know of the First Vision or believed the Moroni visitation to be Joseph’s earliest divine encounter.

This narrative move has led some critics to argue that the First Vision was a later invention and that Joseph initially believed Moroni’s appearance was his first theophany. However, this interpretation collapses under close examination of both Oliver’s own language and the documentary evidence available at the time he was writing.

By 1834, Joseph Smith had already recorded an account of his First Vision in his 1832 history, in which he explicitly stated that he “saw the Lord.” There is substantial evidence that Oliver Cowdery had access to this document while preparing his history. Not only was Oliver serving as Church historian at the time, but there are also striking verbal and thematic correlations between Joseph’s 1832 account, Oliver’s 1834–1835 history, and Joseph’s 1835 journal entry describing the same events.

Rather than being ignorant of the First Vision, Oliver appears to have assumed its reality and authority—so much so that he felt no need to retell it in detail. Instead, he refers to it obliquely before continuing his narrative with Moroni’s visit.

The most frequently misunderstood statement in Oliver’s February 1835 installment occurs when he minimizes the earlier religious excitement and writes that Joseph sought:

This sentence is often cited as evidence that Joseph doubted the existence of God prior to 1823. However, the grammatical structure and narrative framing show that Oliver is referring retrospectively to Joseph’s earlier state of concern, not his condition at age seventeen. The “religious excitement” is explicitly described as a past experience, tied to Joseph’s youth and spiritual anxiety, not as his settled worldview.

Immediately following this statement, Oliver affirms that Joseph’s seeking had already been answered. He writes:

The phrase “long since” signals that the divine response occurred prior to the events Oliver is about to describe—namely, the visit of Moroni. In other words, Oliver is assuring readers that Joseph’s earlier plea for divine confirmation had already been answered, even though Oliver does not recount the vision explicitly.

Oliver Cowdery’s decision to move directly to Moroni’s visit after alluding to Joseph’s earlier divine encounter appears to be a stylistic and narrative choice, not a theological one. The second installment functions as a transition from Joseph’s preparatory spiritual experiences to the beginning of his prophetic commission tied to the coming forth of the Book of Mormon.

Far from denying the First Vision, Oliver signals its reality while choosing to focus on subsequent events. His language affirms that something decisive and correct had already taken place in Joseph’s life—a divine response consistent with Joseph Smith’s own accounts.

Oliver Cowdery did not claim that Joseph Smith lacked belief in a Supreme Being until 1823, nor did he deny or replace the First Vision with Moroni’s appearance. When read carefully, Oliver’s history presupposes Joseph’s earlier encounter with God and reflects familiarity with Joseph’s 1832 account. The much-discussed phrase “if a Supreme being did exist” describes Joseph’s earlier religious questioning, not his final understanding.

Rather than undermining Joseph Smith’s First Vision, Oliver Cowdery’s history quietly affirms it—demonstrating that by the mid-1830s, the experience was known, authoritative, and foundational, even when not retold in full detail.[23]

One of the most persistent criticisms of Joseph Smith’s First Vision accounts is the claim that he had already concluded—before going to the grove to pray—that all churches were false. According to this argument, statements in Joseph’s earliest account (1832) indicate that he had already determined that “there was no society or denomination” built upon the New Testament. This, critics argue, contradicts later accounts in which Joseph expresses uncertainty about which church was true and even surprise upon being told by God to join none of them.

A careful examination of the historical record shows that this criticism rests on a false dilemma. Joseph Smith did not enter the grove having definitively decided that all churches everywhere were false. Rather, the evidence consistently portrays a young seeker who had become deeply disillusioned with the denominations known to him, yet remained uncertain about his duty and still hoped that God would identify the true path.

Critics typically point to an apparent tension between two sets of statements:

From this contrast, critics argue that Joseph had already concluded that all churches were false in 1832 but later revised his story to portray himself as uncertain in order to heighten the drama or doctrinal implications of the First Vision.

This conclusion, however, misunderstands both the scope of Joseph’s early conclusions and the language he used to describe them.

The 1832 account explains how Joseph reached his preliminary conclusions. From roughly age twelve onward, he studied the Bible and compared it to what he observed among the Christian denominations in his area. His conclusions were based on his “intimate acquaintance with those of different denominations,” not on abstract knowledge of Christianity worldwide.

When Joseph wrote that “there was no society or denomination that built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ,” the context suggests a judgment about the denominations with which he was familiar, not a settled conclusion about every church on earth. This reading is reinforced by contemporaneous evidence. An 1832 newspaper report stated that Joseph “had not attached himself to any party of Christians, owing to the numerous divisions among them, and being in doubt what his duty was, he had recourse to prayer.”

In other words, Joseph’s scripture study had led him to doubt the adequacy of the denominations he knew—but not to certainty about what he should do instead. His conclusions intensified his confusion rather than resolved it.

This same uncertainty appears consistently in Joseph’s later accounts. In his 1835 diary entry, he wrote that he “knew not who was right or who was wrong” and felt it was “of the first importance” to determine the truth because of the eternal consequences involved. In the 1838 account, he explained that he was too young and inexperienced “to come to any certain conclusion who was right, and who was wrong,” despite his growing concerns about religious corruption.

This is not a retreat from an earlier certainty but an acknowledgment that Joseph’s personal conclusions were insufficient. The fact that he had already identified serious doctrinal problems did not give him confidence to act decisively. Instead, it convinced him that only divine revelation could settle the matter.

One frequently cited objection focuses on Joseph Smith–History 1:18–19, where Joseph says that it “had never entered into my heart” that all churches were wrong, even though earlier he had asked whether “they were all wrong together.” At face value, this appears contradictory.

However, the phrase “entered into my heart” carries a specific meaning in Joseph’s religious vocabulary. Joseph used similar language elsewhere to describe moments of spiritual certainty rather than mere intellectual consideration. Something could pass through the mind without being fully accepted or internalized at the level of conviction.

Thus, Joseph could consider the possibility that the local denominations were all in error without emotionally or spiritually accepting the idea that no true church existed anywhere. Indeed, a draft history recorded by scribe Howard Coray clarifies this point by stating that Joseph “supposed that one of them were so”—that is, he still believed that at least one sect might be right, even if he had doubts.

Another key insight comes from reading Joseph Smith–History 1:10–18 as a continuous thought rather than isolated verses. In the passages immediately preceding Joseph’s famous question, he specifically names the Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists as the denominations contending around him. His question—“Who of all these parties are right?”—naturally refers back to those groups.

Read this way, Joseph was asking whether the prominent denominations in his area were correct—or whether they were all mistaken—not whether Christianity itself had entirely vanished from the earth. If so, the later instruction to “join none of them” because all were wrong—apparently without geographical or denominational limitation—could well have been surprising and spiritually jarring.

Orson Pratt’s 1840 account further undermines the idea that Joseph had already settled the question. Pratt reports that Joseph reflected on the existence of “many hundreds of different denominations” worldwide and wondered whether any of them constituted the Church of Christ. This expansive view makes little sense if Joseph had already concluded that all churches everywhere were false. Instead, it portrays a young man hoping—however uncertainly—that somewhere among the many sects was the truth.

The historical evidence does not support the claim that Joseph Smith definitively concluded before the First Vision that all churches were false. Rather, it shows that he became increasingly aware of doctrinal corruption and religious division among the denominations he knew, which deepened his uncertainty and led him to seek divine guidance.

Joseph’s scripture study created a crisis, not a resolution. He doubted the churches around him, questioned the integrity of their teachings, and mourned the spiritual condition of the world—but he did not claim the authority or certainty to declare universal apostasy on his own. That determination, according to all accounts, came only through revelation.

Thus, far from undermining the First Vision narratives, the apparent tension between the accounts reflects a realistic process of religious searching: growing doubt, unresolved questions, and the decision to seek answers from God rather than from human judgment alone.

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now