Richard G. Turley, Jr. (Managing Director, Family and Church History Department),

President Young’s express message of reply to Haight, dated September 10, arrived in Cedar City two days after the massacre. His letter reported recent news that no U.S. troops would be able to reach the territory before winter. "So you see that the Lord has answered our prayers and again averted the blow designed for our heads," he wrote.

"In regard to emigration trains passing through our settlements," Young continued, "we must not interfere with them untill they are first notified to keep away. You must not meddle with them. The Indians we expect will do as they please but you should try and preserve good feelings with them. There are no other trains going south that I know of[.] [I]f those who are there will leave let them go in peace. While we should be on the alert, on hand and always ready we should also possess ourselves in patience, preserving ourselves and property ever remembering that God rules."

: It is claimed that Brigham Young ordered the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Source(s) of the criticism

- ↑ This section is derived, with permission, from David Keller, "Thomas Alexander’s Arrington Lecture on the MMM," fairblog (16 January 2008). Due to the nature of a wiki project, it may have had alterations and additions since that time.

- ↑ Thomas G. Alexander, Brigham Young, the Quorum of the Twelve, and the Latter-Day Saint Investigation of the Mountain Meadows Massacre: Arrington Lecture No. Twelve (Arrington Lecture Series) (Utah State Special Collection, 2007), ISBN 0874216877. Alexander's footnotes are below:

- [95] Historian’s Office Journal. July 5, 1859, Carruth transcription of Deseret Alphabet entry.

- [96] Ibid..

- [97] Ibid.

- [98] Historian’s Office Journal, May 25, June 18, and July 5, 1859, Carruth transcription of Deseret Alphabet; George A. Smith so William H. Dame, June 19, 1859, Historian’s Office Letterpress copybooks 1854—1879, 1885—1886, 2:127, Church Archives; Lee, Mormon Chronicle, 1:214 (August 5[6], 1859).

- ↑ Robert D. Crockett, "A Trial Lawyer Reviews Will Bagley's Blood of the Prophets," FARMS Review 15/2 (2003): 199–254. off-site Headings and minor punctuation changes for clarity have been added; footnotes have been omitted. Readers are advised to consult the original review.

- ↑ Robert D. Crockett, "A Trial Lawyer Reviews Will Bagley's Blood of the Prophets," FARMS Review 15/2 (2003): 199–254. off-site Headings and minor punctuation changes for clarity have been added; footnotes have been omitted. Readers are advised to consult the original review.

- ↑ Will Bagley, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), 217–235.; David L. Bigler, Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847–1896 (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1998), 243–252. (bias and errors) Review; Sally Denton, American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, (Secker & Warburg, 2003), 209.

- ↑ Robert D. Crockett, "A Trial Lawyer Reviews Will Bagley's Blood of the Prophets," FARMS Review 15/2 (2003): 199–254. off-site Headings and minor punctuation changes for clarity have been added; footnotes have been omitted. Readers are advised to consult the original review.

- ↑ Robert D. Crockett, "A Trial Lawyer Reviews Will Bagley's Blood of the Prophets," FARMS Review 15/2 (2003): 199–254. off-site Crockett's footnotes are reproduced in the cited material below.

- ↑ Dimick B. Huntington, diary, MS 1419 2, Family and Church History Department Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter Church Archives), 13—14. Bagley interpolates "allies" where "grain" should be used. I think Bagley's conclusion is wrong. See Lawrence Coates, "Review of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows," Brigham Young University Studies 31 no. 1 (January 2003), 153–. off-site. [Crockett's skepticism is well-founded. See conclusive evidence that Bagley misreported the contents of Huntington's journal, which read grain, not allies! Details: W. Paul Reeve and Ardis E. Parshall, "review of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, by Will Bagley," Mormon Historical Studies (Spring 2003): 149–157. Wiki details here.]

- ↑ Most historians will probably believe that "B" refers to Brigham Young. I have my doubts, but it probably makes little difference to the analysis. Wilford Woodruff verifies that a meeting occurred that day with Brigham Young, so the "B" may be "Brigham." However, nowhere else in the diary is Brigham referred to as "B" (but usually as "Brigham") and, indeed, "B" appears as someone else earlier in the diary—possibly Ben Simonds, who has been alternatively described as a Delaware Indian, a half-breed, or a white Indian trader. Huntington, diary, 1. The diary is reproduced at www.mtn-meadows-assoc.com; search "Dimick"; select depoJournals/Dimick/Dimick.2.htm (accessed 14 January 2004).

- ↑ Furniss, Mormon Conflict, 163.

- ↑ John D. Lee purportedly recounts a conversation he translated for George A. Smith to the Indians, although Lee is not a good source for translated dialogue; one should doubt Lee's ability to complete the translation: "The General told me to tell the Indians that the Mormons were their friends, and that the Americans were their enemies, and the enemies of the Mormons, too; that he wanted the Indians to remain the fast friends of the Mormons, for the Mormons were all friends to the Indians; that the Americans had a large army just east of the mountains, and intended to come over the mountains into Utah and kill all of the Mormons and Indians in Utah Territory." William W. Bishop, ed., Mormonism Unveiled: or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop, John D. Lee (St. Louis: Bryan, Brand, 1877; reprint, Salt Lake City: Utah Lighthouse Ministry, n.d.), 223. Although I have doubts about this encounter, it shows that Mormon leaders, when they referred to the Americans, referred to the advancing armies and not emigrants.

- ↑ Huntington, diary, 11—12.

- ↑ Indian Superintendent Garland Hurt determined for himself after the massacre that Brigham Young sought Indian help to run cattle off. Northern Indian tribes told him that "Dimic B. Huntington (interpreter for Brigham Young) and Bishop West, of Ogden, came to the Snake village, and told the Indians that Brigham wanted them to run off the emigrants' cattle, and if they would do so they might have them as their own." Hurt continues: "I have frequently been told by the chiefs of the Utahs that Brigham Young was trying to bribe them to join in rebellion against the United States . . . on conditions that they would assist him in opposing the advance of the United States troops." Garland Hurt to Jacob Forney, 4 December 1857, 35th Cong., 1st sess., H. Exec. Doc. 71, serial 956, p. 204. Huntington's diary account of the event and Hurt's thirdhand account conflict. Huntington's diary does not include a specific request to run off the cattle of emigrants, but appears to be limited to a request to run off the army's cattle. Hurt's thirdhand account of Huntington's statement, which Hurt reported after the massacre became public knowledge, includes a request to run off the army's cattle. Given Hurt's well-acknowledged hostility to Brigham Young, I would view Hurt's statement about emigrants' cattle as a probable exaggeration. But, it is not unreasonable to think that Huntington's vocalized strategy to the Indians was to obstruct overland traffic by running everyone's cattle off.

- ↑ T.B.H. Stenhouse, Rocky Mountain Saints: a full and complete history of the Mormons, from the first vision of Joseph Smith to the last courtship of Brigham Young (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1873), 378.

- ↑ Robert H. Briggs, "Wrestling Brigham," review of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, by Will Bagley, Sunstone, December 2002, 63. Wilford Woodruff, who met the Indian chiefs but was not invited to the hour-long meeting with them, noted in his journal on that date that twelve Indian chiefs from various tribes were in attendance. Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 9 vols., ed., Scott G. Kenny (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985). ISBN 0941214133.

- ↑ For a discussion of the Fancher train's progress, see Donald R. Moorman with Gene A. Sessions, Camp Floyd and the Mormons: The Utah War (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1992), 128: "Traveling in two sections, the train weathered the journey across the plains and gave every indication that it intended to pursue the snow-free southern route to California." Federal surveyor Lander described the "southern route" in F. W. Lander to W. M. F. Magraw, 1859, 35th Cong., 2nd sess., H. Exec. Doc. 108, serial 1008, pp. 63—65. A federal surveyor described the southern route as the route from "St. Louis to Salt Lake City, as above; thence by way of Vegas de Santa Clara and Los Angeles." J. H. Simpson to Office of Topographical Engineers, Department of Utah, 22 February 1859, 35th Cong., 2nd sess., S. Exec. Doc. 40, serial 984, p. 37. Describing Simpson's report, one historian writes about the "northern route along the Oregon Trail" and all other roads to the south. W. Turrentine Jackson, Wagon Roads West: A Study of Federal Road Surveys and Construction in the Trans-Mississippi West 1846—1869 (1952; reprint, with foreword by William H. Goetzmann, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1965), 29.

- ↑ Huntington, diary, 14. See also discussion of this date in Coates, review of Blood of the Prophets.

- ↑ As explained at the end of this review, the Paiutes were the poorest of the poor among Indians. Regarding the Paiutes and horses, as one article in the Salt Lake Tribune notes: "The Utes, who exchanged the Indian slaves they captured for horses, were known for their business acumen. But not the Paiutes. 'The Paiutes just ate them.'" Mark Havnes, "Spanish Trail Given National Designation," Salt Lake Tribune, 24 March 2003, sec. D.

- ↑ Bishop, Mormonism Unveiled, 252.

- ↑ Robert K. Fielding, ed., The Tribune Reports of the Trials of John D. Lee for the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (Higganum, Conn.: Kent Books, 2000), 297; Kenney, Wilford Woodruff's Journal, 5:98; Huntington, diary, 14.

- ↑ Aguilar v. Atlantic Richfield Co., 25 Cal. 4th 826, 852, 107 Cal. Rptr. 2nd 841, 863 (2001).

- ↑ Briggs, "Wrestling Brigham," 65.

- ↑ David J. Whittaker, "'My Dear Friend': The Friendship and Correspondence of Brigham Young and Thomas L. Kane," Brigham Young University Studies 48 no. 4 (2009), 212. [Citation: Young to Kane, December 15, 1859. Young included in this letter a copy of George A. Smith’s letter to Young regarding the massacre, dated August 17, 1858. Both letters are in Thomas L. Kane Correspondence, Perry Special Collections.]

Response to claim: 210 - Brigham is said to have ordered the cross and cairn at Mountain Meadows torn down

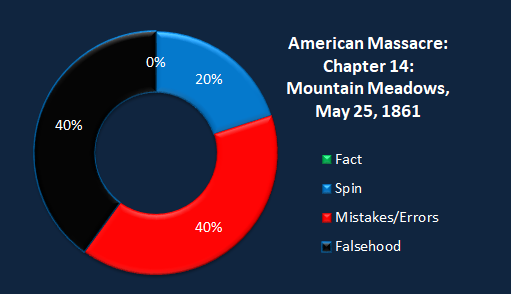

The author(s) of American Massacre make(s) the following claim:

Brigham is said to have ordered the cross and cairn at Mountain Meadows torn down.

Author's sources:

- Wilford Woodruff journal, May 25, 1861.

FAIR's Response

Fact checking results: This claim is false

Neither Wilford Woodruff, nor John D. Lee said anything in their journals about Brigham Young ordering the destruction of the monument.

Question: Did Brigham Young order that the Mount Meadows monument be destroyed?

Neither Wilford Woodruff, nor John D. Lee said anything in their journals about Brigham Young ordering the destruction of the monument

The critical book One Nation Under Gods claims that when Brigham Young visited the Mountain Meadows Massacre site in 1860 and saw the monument, that he "ordered the monument and cross torn down" and demolished. [1]

If Brigham Young had ordered the monument's destruction, this would be an unfortunate example of the fallibility of mortal prophets. The ability of Lee and others to hide their crimes for a time is not unexpected given LDS doctrine (D&C 10꞉37).

Wilford Woodruff (and John D. Lee) said nothing in his journal about Brigham Young ordering—or desiring— the destruction of the monument. Waite's book reports a rumor, and Leavitt's account is frank to admit that all Brigham did was "raise his arm to the square" (this gesture is used, for example, during LDS baptisms to indicate that the priesthood is being invoked, and a covenant made). Leavitt presumes that Brigham wanted the monument destroyed, but this was his supposition. It is completely unsupported by Woodruff, and it is completely inconsistent with Lorenzo Brown's witness of three years later that the monument was still standing.

The author's claim that Wilford Woodruff's journal supports the destruction of the monument is absolutely unsupportable. It is certainly not a historical certainty that Brigham Young ordered the monument destroyed. The Leavitt account tells us only that some Church members interpreted Brigham's actions in that manner—we thus cannot rule out an intention by Brigham to have the monument destroyed, but historians are less skilled at mind-reading than even Dudley Leavitt would have been.

One Nation Under Gods gets the date and reference to Woodruff's diary wrong—the reference is to 1861, not 1860. But, there are more serious lapses.

Woodruff journal: There is no mention of Brigham Young tearing down the cross or demolishing the monument

The quote from Woodruff's journal reads simply:

25 A vary Cold morning. Much Ice on the Creek. I wore my great Coat & mittens. We visited the Mountain Meadow Monument put up at the burial place of 120 persons killed by Indians in 1857. The pile of stone was about 12 feet high, but begining to tumble down. A wooden Cross was placed on top with the following words: Vengence is mine and I will repay saith the Lord. President Young said it should be Vengence is mine and I have taken a little.

There is no mention of Brigham Young tearing down the cross or demolishing the monument—Woodruff noted that the monument was already "begining [sic] to tumble down," but said nothing about Brigham ordering it torn down.

Brooks: the monument was still standing three years after Brigham's first visit to the monument

The Brooks account is more on point. In favor of the claim that Brigham had something to do with the monument's destruction, Brooks cites:

- her grandfather, Dudley Leavitt, to one of his sons, who recorded it: "‘I was with a group of elders that went out with President Young to visit the spot in the spring of ’61. The soldiers had put up a monument, and on top of that a wooden cross with words burned into it, ‘Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord, I will repay.’ Brother Brigham read that to himself and studied it for a while and then he read it out loud, ‘Vengeance is mine saith the Lord; I have repaid.’ He didn’t say another word. He didn’t give an order. He just lifted his right arm to the square, and in five minutes there wasn’t one stone left upon another. He didn’t have to tell us what he wanted done. We understood.’"

- Catherine Waite's book (which has a footnote which quotes from General Carlton) states that "this monument is said to have been destroyed the first time Brigham visited that part of the Territory" (Waite, The Mormon Prophet and his Harem, 71).

Brooks also cites the Lorenzo Brown diary from July 1, 1864 wherein he states that he passed by, and saw the monument still standing. This was three years after Brigham's first visit to the monument. It is possible that this was a rebuilt monument, but the description is strikingly similar:

went past the monument that was erected in commemoration of the Massacre that was committed at that place by officers & men of Company M Calafornia volunteers May 27 & 28 1864 It is built of cobble stone at the bottom and about 3 feet high then rounded up with earth & surmounted by a rough wooden cross the whole 6 or 7 feet high & perhaps 10 feet square On one side of the cross is inscribed Mountain Meadow Massacre and over that in smaller letters is vengeance is mine & I will repay saith the Lord. On the other side Done by officers & men of Co. M Cal. Vol. May 27th & 28th 1864 Some one has written below this in pencil. Remember Hauns mill and Carthage Jail….’[2]

Brigham H. Roberts adopted a similar view, writing, "later was destroyed either by some vandal’s hand or the ruthless ravages of time…. The destruction of this inscription is unjustly connected by the judge with President Young’s first visit to southern Utah after it was erected (1861)."[3]

Uncited material: John D. Lee says nothing about demolishing the monument

One Nation Under Gods does not mention the John D. Lee diary, which contains a second-hand account of Brigham Young proceeding "by way of Mountain Meadows." Lee says nothing about demolishing the monument.[4] He was to record Brigham's words as preserved by Woodruff six days later, so he clearly had an interest in the matter. An order for destruction or the actual event of destruction of the monument would arguably have been something he would have recorded had he heard about it.

Regardless of whether the Mormons actually dismantled the monument, later that same year (1861) there was torrential rain and snow that devastated parts of southern Utah and actually changed some of the landscape. If the monument was still standing prior to the heavy storms, it may not have been after the storms. In the following years, the monument was built up and torn down by various groups of people passing through.[5]

Response to claim: 215 - The "entire blame of the massacre was shifted to" John D. Lee's shoulders

The author(s) of American Massacre make(s) the following claim:

The "entire blame of the massacre was shifted to" John D. Lee's shoulders.

Author's sources:

- Brooks, John Doyle Lee, 296.

FAIR's Response

Fact checking results: This claim is false

This is clearly false. Contemporary government documents show that federal officials continued to "show...efforts by the federal machinery to prosecute others for at least eight years after Lee's trial."

[6] If blame rested on Lee alone, this would make no sense.

Did Brigham Young block prosecution of the individuals responsible for the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

Brigham Young's presidential office journal (and other items) makes it clear that federal prosecutors are the most responsible for not bringing the perpetrators to justice

Critics charge that Brigham Young blocked prosecution of those who committed the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

LaJean Purcell Carruth deciphered Brigham Young's presidential office journal (and other items) written in Deseret Alphabet. This newly discovered information makes it clear that federal prosecutors —not Brigham Young!—-are the most responsible for not bringing the perpetrators to justice.[7] Thomas Alexander writes:

On July 5, 1859, after the public knew that Cumming had received word from Washington placing the army under the governor’s control, Young met with George A. Smith, Albert Carrington, and James Ferguson. They discussed the "reaction to the Mountain Meadow Massacre." Young told them that US. attorney Alexander Wilson had called "to consult with him about making some arrests of" the accused.[95]

On the same day, Wilson had met with Young. Young told him "that if the judges would open a court at Parowan or some other convenient location in the south, .. . unprejudiced and uninfluenced by. . . the army, so that man could have a fair and impartial trial He would go there himself, and he presumed that Gov. Cumming would also go . . . " He "would use all his influence to have the parties arrested and have the whole. . . matter investigated thoroughly and impartially and justice meted out to every man." Young said he would not exert himself, however, "to arrest men to be treated like dogs and dragged about by the army, and confined and abused by them,’ presumably referring to the actions of Cradlebaugh and the army in Provo. Young said that if the judges and army treated people that way, the federal officials "must hunt them up themselves."[96]

Wilson agreed that it was unfair "to drag men and their witnesses 200 or 300 miles to trial." Young said "the people wanted a fair and impartial court of justice, like they have in other states and territories, and if he had anything to do with it, the army must keep its place." Wilson said he felt "the proposition was reasonable and he would propose it to the judges."[97]

Now confident that the army would not intrude and abuse or murder Mormons, and that the US. attorney and governor would support them, the church leaders lent their influence to bringing the accused into court. On June 15, 1859, to prepare the way for the administration of justice, Brigham Young had told George A. Smith and Jacob Hamblin that "as soon as a Court of Justice could be held, so that men could be heard without the influence of the military he should advise men accused to come forward and demand trial on the charges preferred against them for the Mountain Meadow Massacre" as he had previously done. Then he again sent George A. Smith and Amasa Lyman south, this time to urge those accused of the crime to prepare for trial and to try to suppress Mormon-authored crime[98].[8]

However, Utah's governor felt that any such crimes would be covered by the post-Utah war amnesty.

Source(s) of the criticism

Critical sources |

- Richard Abanes, One Nation Under Gods: A History of the Mormon Church (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2003), 243–252 ( Index of claims )

- Will Bagley, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), 217–235.

- David L. Bigler, Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847–1896 (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1998), ??. (bias and errors) Review

- Sally Denton, American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, (Secker & Warburg, 2003), 209.

- Jon Krakauer, Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith (Anchor, 2004), ??.

|

Was prosecution of those responsible for Mountain Meadows Massacre blocked by the Church?

There is no evidence the Church blocked prosecution of the Massacre perpetrators

It is claimed that actions of Brigham Young and the institutional Church and/or local Mormons prevented federal officials from prosecuting those guilty of the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

There is no evidence the Church blocked prosecution of the Massacre perpetrators. There is substantial evidence that poor federal organization, infighting, and refusal to deputize LDS lawmen played a role in slowing the process. When presented with evidence by lawful authorities, LDS juries returned indictments.

- The post-Utah war amnesty led some non-members to believe that the massacre was covered under the presidential amnesty.

- There was a long-running dispute over jurisdiction and tactics between the judiciary and the executive (i.e., federal prosecutor) branches. This had nothing to do with the Mormons, but hampered prosecution.

- Disputes between the above groups also led to difficulties with the army, something also not under Mormon control or influence.

- Judges' meddling in the arrest process made it virtually impossible to properly arrest and indict perpetrators.

- The grand jury in southern Utah was never asked to indict anyone for the Massacre during their first session. When presented with the opportunity, they returned indictments later that same year.

- The Mormons did not, as claimed, insist on the right to dictate who sat on petit juries. Other federal officials declared this to be completely false.

- Federal officials and judges refused to deputize or use LDS lawmen to make arrests.

- The U.S. attorney general refused the district attorney's request to reopen the investigation in 1872—once again, this was beyond the Mormons' control or influence.

- Brigham Young had been relieved of his position as territorial governor. He had no secular authority to directly arrest or charge perpetrators.

One reviewer described the difficulties with this theory: [9]

The Amnesty

- Blood of the Prophets has charged high-ranking church officials with two decades of obstructing the federal investigation. Bagley's emphasis is in Mormon history, so he sometimes shows his lack of breadth in political and social matters that originate outside the Great Basin. One of the areas in which he displays this weakness is his failure to discuss the effect of President Buchanan's general amnesty upon the massacre prosecutions (p. 205).

- [U.S. President] Buchanan issued an amnesty for all crimes of the Mormons related to the claimed acts of sedition and treason [during the U.S. army's assignment to Utah in the abortive "Utah War"]. Governor Alfred Cumming announced a broad interpretation of that amnesty to the Saints on 14 June 1858. Certainly, by the date of the amnesty, federal officials believed that Mormons had directed the massacre, and they believed that John D. Lee was one of the leaders. One might reasonably conclude that the amnesty was intended to cover the massacre participants.

- Some in the federal government and the press believed that Buchanan intended to pardon the massacre perpetrators. Indian superintendent Jacob Forney was so upset with U.S. District Court Judge John Cradlebaugh's massacre investigation that he cursed Cradlebaugh's name, citing the amnesty as the basis for his objections, or so we are told from a source hostile to Forney. Non-Mormon U.S. District Attorney Alexander Wilson and non-Mormon U.S. District Court Judge Charles C. Sinclair disagreed over the application of the amnesty, with Wilson refusing to present to the jury bills of indictment. Harper's Weekly noted the conflict over the amnesty in the prosecution of the massacre. The New York Post opined that the amnesty excused the massacre crimes because it was an aspect of the Utah war intended to come within the amnesty's scope. It is no wonder that prosecution was uncertain. But, given the controversy the amnesty sparked in the Eastern press with regard to the massacre investigation, it seems that Blood of the Prophets would have discussed it. This is a significant omission.

Disputes between the executive and judicial branches

- The presidential amnesty contributed to the lengthy delay in federal prosecution. In addition, the federal judiciary and federal prosecutor fought over control of the massacre investigation. This internecine dispute stymied federal investigation of the massacre for several years. Bagley does not discuss this feud as a source for delay.

- At the national level in the early nineteenth century, the federal judiciary and the prosecutors repeatedly jockeyed for power in ways that would appear unseemly today. Thomas Jefferson said that the "great object of my fear is the federal judiciary. That body, like gravity, ever acting with noiseless foot & unalarming advance, [is] gaining ground step by step. . . . Let the eye of vigilance never be closed." He condemned the judiciary's usurpation of the legislative prerogatives with its pious interpretation of its own brand of Christianity.55 The U.S. Constitution gives little direction to the judiciary compared to what it gives to the legislative and executive branches. The Hamiltonian Federalists saw the federal judiciary as a way to expand federal power and to crush state self-determinism (read: slavery). The Jeffersonian republicans believed states' rights were paramount except as to powers specifically delegated to the federal government. The Federalist judiciary gained the upper hand with the enforcement of the Sedition Act of 4 July 1798, which crushed Jeffersonian dissent. As historian James Simon explains, their "blatantly partisan actions [of stifling criticism of the John Adams administration] in pursuit of convictions under the Sedition Act reinforced Jefferson's profound distrust of the federal judiciary." Supreme Court Justice Salmon Chase's prosecutions under the Sedition Act, while a sitting Supreme Court justice, were notorious, eventually leading to an attempt to remove him by impeachment.

- Utah's federal judges replayed this high national drama on a frontier stage. As with the amnesty, Blood of the Prophets fails to see the broad political and social issues of the struggle for federal power. Brigham Young's demand for local self-determinism replaced Thomas Jefferson's urbane urge for state self-determinism. Polygamy, rather than slavery, was an affront to federal power and needed to be crushed. In the early days of Utah, federal judges of questionable character—a point Van Vliet conceded—directed the investigation of crime, requested army troops to march against the local citizenry, harangued citizens in their places of worship about the lack of virtue in their plural wives, and testified in Congress about Mormon debauchery. These judicial efforts to crush the Mormon theocracy would be unthinkable today in any social context.

- Blood of the Prophets accepts Cradlebaugh's account of the dispute uncritically, condemning the U.S. district attorney as "pliant" (p. 235) and "'closely allied to the Mormons by some mysterious tie'" (p. 217) for failing to do anything about the massacre. Citing Cradlebaugh and Sinclair, we are told that Wilson's "whole course of conduct has been marked with culpable timidity and neglect." Bagley would have us believe that the U.S. district attorney was too cozy with the Mormons and that the Mormons lobbied him to ignore the massacre.

- The official correspondence, however, shows that the executive and judicial branches of government distrusted each other and that neither was effective in the prosecution of the massacre. The purported investigation began, at least in Cradlebaugh's view, with grand jury proceedings from 8 to 21 March 1859 in Provo. Mormon accounts say Cradlebaugh called out the army to terrorize the local Provo population with the might of federal power. Cradlebaugh and Bagley assert that the troops were necessary to protect the court and witnesses from Mormon Danite assassins. Governor Cumming sided with the Mormons, who were outraged with Cradlebaugh's use of the troops. Cumming believed that he, as the federal executive, had the sole civilian authority to call out the troops in the Territory.

- Attorney General Black in Washington, D.C., said that it was not Cradlebaugh's job to determine whom to prosecute or when to call out the troops. He instructed U.S. District Attorney Wilson to "oppose every effort which any judge may make to usurp your functions. . . . If the judges will confine themselves to the simple and plain duty imposed upon them by law of hearing and deciding the cases that are brought before them, I am sure that the business of the Territory will get along very well."

- President Buchanan approved of Wilson's efforts to resist the judiciary's incursion into his prerogatives and the use of federal troops. General Albert Sidney Johnston, commanding Camp Floyd, implied that he was unhappy being called into the fray to support the judiciary.

- Black attempted to rein in the Utah judges, explaining to them the judiciary's function to "hear patiently the causes brought before them." The executive branch has a "public accuser, and a marshal." As the U.S. Supreme Court said in an 1868 landmark case, public prosecutions are within the exclusive jurisdiction of the U.S. district attorney until indicted offenses are in trial before a petit jury. Judges have no role in prosecutions until then.

- Addressing a defensive letter to President Buchanan, Cradlebaugh and fellow judge Charles Sinclair admitted that "the difficulty [which has] arisen between the judiciary and executive is deeply to be deplored." Nonetheless, the judges attacked Governor Cumming and U.S. District Attorney Wilson for failing to faithfully execute their duties, especially in connection with the 1859 Provo grand jury.

- Cradlebaugh's grasping for prosecutorial power made prosecution nigh impossible. Prosecutors must work with judges to obtain warrants and convene grand juries, but Cradlebaugh would not cooperate. He complained to Buchanan that Wilson refused to execute (i.e., serve) bench warrants for witnesses, but Wilson countered that Cradlebaugh would not give him the warrants for execution. Wilson wanted the massacre grand jury to be empanelled in southern Utah, close to the scene. He also urged the Justice Department to provide funds "to enable the officers of the court to make a patient and thorough search for evidence." Cradlebaugh (remember, he is the judge, not the prosecutor) responded to Wilson's request by traveling to Santa Clara and issuing arrest warrants in 1859. None of them were executed. Why not? Cradlebaugh failed to include in his entourage the person with prosecutorial discretion, the U.S. district attorney. He further refused to respond to Wilson's request for information about the warrants so that they could be served. Cradlebaugh also refused to tell Wilson about his activities in Santa Clara. Blood of the Prophets does not explain how the prosecutor could be expected to prosecute when the judge shuts him out of the process.

- The significance of this episode is unmistakable. The prosecution delayed as it resisted the judiciary's grasping for control of the massacre investigation. This material escapes Bagley.

Mormons would not indict in 1859 grand jury?

- According to Bagley, the 8—21 March 1859 grand jury proceedings in Provo provide a lurid but relevant detour in the story of the massacre prosecutions. He uses the story of the grand jury to show that Mormons obstructed prosecutions by refusing to indict their own for the massacre and for other crimes. The book claims that the grand jury "'utterly refused to do anything'" about the massacre and other crimes against non-Mormons. Thus the federal grand jury "ground to a halt" (p. 218). The implication of Bagley's claim is that church authorities instructed grand jurors to obstruct voting when bills for indictment against Mormons were presented to them. Bagley, however, has missed primary source material which contradicts his conclusions.

- This tale of the grand jury is central to one of Bagley's more salacious themes. Blood of the Prophets paints a picture of a community of priests dripping in gentile blood, with Mormon laity thumbing their noses as federal authorities sought to staunch the flow. Bagley and Cradlebaugh make much of the all-Mormon Provo grand jury's failure to return any criminal indictments, including in the notorious Parrish and Potter case and the Henry Jones case. Blood of the Prophets does not have the facts right in the Henry Jones case, confusing it with a different and unrelated crime. Bagley tells us that church authorities obstructed not only the massacre investigation, but also the investigation of other notorious crimes for which, he says, there were never any indictments (pp. 75—76).

- The official correspondence refutes these claims. Bagley has the facts wrong because he does not rely upon the official files. U.S. District Attorney Wilson's diary (again, it was his duty to bring indictments, not Cradlebaugh's) and his report to the U.S. attorney general indicate that no indictment was obtained from the Provo grand jury for the Mountain Meadows Massacre because none was requested by the U.S. district attorney. Yes, Judge Cradlebaugh may have asked for indictments in his initial charge, but this was an empty request because it was not his lawful request to make. It was U.S. District Attorney Wilson's job alone to control the grand jury's reception of evidence and the timing of decision. Wilson never asked the grand jury to indict for massacre offenses. The grand jury's term was occupied with other crimes, and then Cradlebaugh discharged the grand jury before Wilson could ask the grand jury to act. An army officer, familiar with the proceedings, opined that the reason Cradlebaugh dismissed the grand jury precipitously was not that Cradlebaugh was upset with its performance, but that General Johnston withdrew Cradlebaugh's army escort. In addition, when a second grand jury was empanelled in 1859, no indictments were sought for the massacre. Yet, Bagley would have us believe on the sole basis of Cradlebaugh's claims that the grand juries refused to indict for the massacre.

- Just as Bagley has the facts wrong about the 1859 grand jury's treatment of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, so does he miss important facts about the grand jury's treatment of other crimes. The second 1859 grand jury handed down indictments for the Parrish and Potter and the Henry Jones cases, yet Bagley tells us that no indictments were ever obtained for these crimes.

Church would not help capture fugitives?

- Bagley claims that high Mormon officials refused to cooperate in apprehending the massacre fugitives. For example, Cradlebaugh reports that he told Buchanan that church officials offered to produce fugitives upon condition that the church dictate the composition of the petit juries. Bagley does not tell us that U.S. District Attorney Wilson declared this "an unqualified falsehood." Mormons did no such thing.

- The federal judiciary denied Mormon law enforcement officers the power to assist federal officers in the pursuit of criminal convictions. Governor Cumming complained that the federal judges refused to admit to the bar federal territorial prosecutors. Indeed, Cradlebaugh and fellow judges refused to permit the Mormon territorial attorney (even though he was technically an officer of the United States) to enter their courtrooms and present bills for indictments.

- U.S. District Attorney Wilson attempted to persuade non-Mormon Deputy U.S. Marshal William Rodgers to effect service of process upon massacre participants. Rodgers rebuffed the request, claiming a lack of resources. Then, on 6 August 1858, Wilson told the federal marshal that the Mormon territorial marshal, John Kay, would accomplish the investigations and the arrests. According to Wilson, "Kay was a Mormon, had a knowledge of the country and of the people, and expressed a determination, if legally deputized, to make arrests if possible." But, Rodgers refused to deputize Kay on the ground that Kay "was a Mormon." For the federal government, a crook on the lam was better than a crook collared by a Mormon.

- The federal marshal was also less than diligent, frequently complaining about a lack of pay. However, federal surveyors had no difficulty locating and using the services of the fugitives. The surveyors' accounts mock the progress of the investigation, recounting jokes with and pranks upon the fugitives. Additionally, in 1872, the U.S. attorney general denied a request by the U.S. district attorney to reopen the investigation of the massacre.

- As another example of silly officiousness, immediately prior to Lee's first trial in 1875, lawyers Jabez Sutherland and George C. Bates offered to surrender indictees William Stewart, Isaac Haight, George Adair, and John Higbee in return for accommodating their request for bail. U.S. District Judge Jacob Boreman was incensed with this proposal, refused it, and instead commenced disbarment proceedings against these lawyers. Blood of the Prophets touches on this briefly but not fairly (p. 290). Although a defense lawyer may not shield a fugitive, it is common for fugitives to negotiate the terms of their surrender indirectly through lawyers. Judge Boreman's 13 February 1875 letter to Sutherland and Bates shows that the judiciary petulantly refused to deal with Mormons or even attorneys for Mormons. The judge condemned Sutherland for taking on a Mormon as a client because Mormons have "the very soul of corruption." Boreman's refusal to discuss bail is ironic in light of the bail he later granted Lee.

- Federal judges denied Mormons permission to assist federal officials with criminal prosecutions. These judges considered Mormons as disloyal "foreigners," as un-American, "perverted, oppressed, [and] alien." Mormons could not be trusted to do anything, including fight crime. Avoiding collaboration with the Mormons was of greater social value than justice.

- Bagley fails to report accurately early efforts at apprehension. Skipping over legitimate offers of help, Bagley accuses the church of obstructing justice by frustrating the investigation. That is not appropriate, given the evidence.

Brigham Young took no official action?

- Blood of the Prophets criticizes Brigham Young for doing nothing in his official capacity to prosecute the massacre (p. 379). Young, however, explained that he took no official governmental action against the perpetrators because President Buchanan stripped him of these powers and Governor Cumming possessed all the powers of the executive. Once he was stripped of civil power, the church may have well taken the position that the Mormon prophet's control over wrongdoers was limited to the remedies specified in section 134 of the church's Doctrine and Covenants. Nothing required Brigham Young to hunt down the participants and turn them over to the very powers seeking to jail him for bigamy (see D&C 134:4).

- There is no competent evidence of a Mormon cabal to influence the executive branch to delay prosecution. There is much speculation, but nothing more. The Eastern press occasionally blamed the delay upon the Buchanan and subsequent administrations. The will to prosecute was not there. Both Cradlebaugh and Wilson gave up and left town before the Civil War. [article cited ends here]

Source(s) of the criticism

Critical sources |

- Will Bagley, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), 217–235.

- David L. Bigler, Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847–1896 (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1998), 243–252. (bias and errors) Review

- Sally Denton, American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, (Secker & Warburg, 2003), 209.

- John Dehlin, "Questions and Answers," Mormon Stories Podcast (25 June 2014).

|

Was there a "deal" made with Brigham Young regarding prosecution for the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

There is no compelling evidence that such a deal was ever made

Critics charge that only a corrupt "deal" with Brigham Young allowed prosecutors to charge and convict anyone with the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

- The continued theory of a deal to offer Lee as a scapegoat lacks competent, much less compelling, evidence. Speculation is a game played by Bagley...but there ought to be more than that.

One reviewer described the difficulties with this theory:

Introduction

- Blood of the Prophets tells us that the U.S. district attorney's office struck a deal with the church: they would offer John D. Lee as a scapegoat to avoid all further prosecutions, and in return the church would help convict Lee in a second trial. For critics of the church (and I would put Blood of the Prophets in this category), the deal and scapegoat story helps sell the idea that the church was not above thwarting justice. For advocates of John D. Lee (and I would put [Juanita] Brooks in this category), the deal and the scapegoat theory helps sell the idea that an innocent Lee was willing to suffer as a martyr for his friends and church.

- The deal is important to Bagley's conclusions. He says: "In a case that threatened to shake the LDS church to its foundations, the prosecutor found he could only secure a guilty verdict with the cooperation of Mormon authorities. As attorneys do, Howard made a deal" (p. 300). As part of this deal, the church assisted Howard with manufactured evidence and manipulated justice (p. 299). Bagley also tells us that U.S. District Attorney Howard was "'on the make,'" or in other words, had been bribed or threatened with blackmail by church leaders (p. 299).

- Bagley's failures in this area are the same as Brooks's and the Salt Lake Daily Tribune's. The latter first floated this theory on 27 September 1876, citing only supposition. So Bagley is in good company.

- ...we will [first] examine the law, which demonstrates that any deal would have been a worthless nullity. We will then look at the evidence Bagley offers to support his theory of a deal, to show that his evidence lacks proper foundation and is thus not reliable. Lastly, we will see from an overwhelming amount of official correspondence that Howard's later actions were inconsistent with any "deal." [10]

The law

- The Law Pertaining to Agreements to Thwart Justice. A "deal" to thwart justice would have been a legal impossibility, a nullity, void at the outset, and obligating nobody. Under English and American common law, certain agreements such as agreements to collect gambling debts incurred in nongambling jurisdictions, to pay for a prostitute, or not to report a crime are unenforceable. Another example of an unenforceable agreement is an agreement to forbear prosecution of a crime. In U.S. v. Ford, an 1878 U.S. Supreme Court decision, the court summarized the law of forbearance of prosecution. A grant of immunity must be approved by a judge and is granted only to accomplices willing to come forward and testify in good faith against an accused. On the other hand, the court said that an executive pardon does not require approval by a judge or does not constitute an agreement to come forward to testify, but it does require a presidential act. A pardon usually comes only after conviction of the to-be-pardoned felon. Thus, the two kinds of deals approved by the Supreme Court require an official stamp of approval by persons other than the prosecutor; secret deals would not work.

- Before the Supreme Court's 1878 decision, grants of immunity were questionable. Prevailing law before U.S. v. Ford suggested that a grant of immunity might not have been enforceable if the person granted immunity "appear[ed] to have been the principal offender" and that the best one could hope for was an "equitable" claim to a presidential pardon. Howard would also have known that an unlawful grant of immunity may have been a crime itself; he could have been subject to prosecution. He was obviously knowledgeable in the area because he appears to have offered John D. Lee a presidential pardon after Lee's conviction.

- Any subsequent U.S. district attorney, or even Howard himself, could have simply ignored a deal to thwart justice and could have prosecuted any person worthy of prosecution. Therefore, if a deal to thwart justice was a nullity at the outset, it seems unlikely that a competent lawyer would have spent any effort reaching such a deal.

Bagley's Evidence of a Deal

- Turning to Bagley's evidence of a deal to make John D. Lee a scapegoat (which really is unnecessary to discuss, given the legal impossibility of such a deal in the first place), we find it wanting. For example, there is no evidence whatsoever, other than reported rumor, that U.S. District Attorney Sumner Howard was bribed.

Witnesses told what to say?

- Nor is there evidence that witnesses were told what to say. Bagley, as does Brooks, says that "according to . . . family traditions," Nephi Johnson and Jacob Hamblin received letters ordering them to testify and "telling them what to say" (p. 304). "Family traditions" are not evidence. I would like to see the letters. What would they have shown? That witnesses were told to lie about Lee's guilt when Lee was not really guilty? It is unlikely that Lee was not guilty. Although there may indeed have been letters telling witnesses to cooperate, it is doubtful that the letters instructed them what to say.

- As further evidence of a deal, Bagley examines Hamblin's role in the second trial. Bagley and the Salt Lake Daily Tribune attack, in particular, Hamblin's testimony that Lee confessed to him and the fact that Hamblin never mentioned the confession to investigating law enforcement officers. They claim that Lee's confession to Hamblin never occurred, and they have suggested that church officials orchestrated Hamblin's testimony to secure Lee's conviction. Brooks agreed with Bagley's later assessment that Hamblin's testimony was selectively truthful and that he "could not remember what he did not want to tell."

- The transcript shows that no lawyer in the second trial pushed Hamblin to say very much although Hamblin said he had more to tell. Each side was undoubtedly fearful to ask questions that would elicit previously unknown answers. Either side could have asked the court to order Hamblin, upon pain of contempt, to tell it all. Neither side did. Had I been the prosecutor, I would not want Hamblin to say anything that might possibly implicate Brigham Young because, in that event, I would have followed the same unsuccessful strategy of grandstanding against Brigham Young as did U.S. District Attorneys William Carey and Robert Baskin in the 1875 trial. Similarly, because Hamblin was under the control of the prosecution, as Lee's defense lawyer I would not know what Hamblin would say. In this particular case, less was more. There is no evidence that Hamblin lied; in fact, Hamblin's recent biographer, Hartt Wixom, takes exception to the charge of perjury. Lee's attorney, Bishop, admitted that Hamblin was an honest man, even though Lee contended that Hamblin's testimony was false. The press may have wished that Hamblin had said more, but Hamblin was not talking to the press.

- A juror's dream has not the slightest chance of constituting evidence, but Bagley offers it to us as such (p. 306). Blood of the Prophets uses juror Andrew Corry's recollection of a conversation he had with another juror about that juror's dream that Lee would be offered as a scapegoat. When Corry executed his affidavit in 1932 he was eighty-four years old. He had probably been pursued for fifty-six years by persons interested in having him support a particular view. The affidavit looks to be too fine a production.

- Corry's affidavit, nonetheless, is compelling to me in a way Blood of the Prophets would not appreciate. Corry does not claim any external pressure to vote for Lee's conviction. He does not mention any pressure by any church authority to vote a particular way. He does not mention a deal. Corry dwells on the scapegoat theory, but that theory was the only defense theory offered by Lee's attorneys and the only possible theory for the jurors to debate. It seems that fifty-six years would have uncovered a claim of church pressure, given Corry's willingness to spill all in his affidavit.

Dictate to jurors?

- Blood of the Prophets tells us that William Bishop, Lee's attorney, claims that he had an agreement with local church authorities to select particular persons as jurors (p. 302). According to Bishop:

- The attorneys for the defendant had been furnished with a list of the jurymen, and the list was examined by a committee of Mormons, who marked those who would convict with a dash (—), those who would rather not convict with a star (*), and those were certain to acquit John D. Lee, under all circumstances, with two stars (**).

- If Bishop asserts, which he really does not, that local church leaders agreed with him to dictate to jurors the outcome of the case, Bishop would be admitting to a crime at the most and grounds for disbarment at the least.

- Blood of the Prophets recounts a story by Frank Lee that each juror favorable to Lee's cause would have a "star pinned under his arm" so that Bishop would know "whom to choose" (p. 302). I don't trust this evidence. According to genealogical records, and Bagley does not mention this, Frank Lee would have been barely thirteen years old by the time of the second trial when he claims that this information was conveyed "in the Council meeting." Frank Lee does not say he was at the meeting. A thirteen-year-old boy, one who had lived in isolation his entire life with his mother Rachel, would not likely understand the intricacies of conspiracies to suborn perjury. How many of the dozens or hundreds of potential jurors would have been trained to display their underarms only to Bishop? What would the stars have looked like? Frank Lee undoubtedly misheard secondhand family accounts of Bishop's list of potential jurors.

- It certainly is not unusual for an experienced trial lawyer in a small town to compile a list of dozens of known veniremen (someone who is summoned to serve on a jury) and rank them according to their proclivities. A trial lawyer will use many sources to learn facts about these potential jurors. Even an experienced lawyer might get too close to potential jurors in the pretrial phase, as Clarence Darrow learned when he was indicted in 1911 in Los Angeles for allegedly offering money to a potential juror before jurors were called. Bishop probably analyzed the pretrial jury pool. His friendly sources were sympathetic Mormons in the community who probably identified to him and Lee those veniremen who might vote Lee's way.

- Bagley and the press also cite as evidence of a deal the fact that an all-Mormon jury was selected for the first trial. Obviously, the argument goes, an all-Mormon jury could be controlled by the church more easily than a part-Mormon jury. Lee's attorney advanced this theory during closing argument. Howard replied by explaining that it was Lee's attorney, not the prosecution, who had struck non-Mormons from the panel. Bishop, said Howard, "was very anxious to get every Gentile off the jury; and I kept striking off Mormons." Because Mormons outnumbered non-Mormons by a huge margin, and because challenges to jurors are typically limited to a certain number per side, it would have been relatively easy for one side to unilaterally control the religious makeup of the jury. According to the uncontested trial transcript, it was Lee's attorney who did this and not, as Bagley argues, Howard. Bishop's unilateral selection of an all-Mormon jury (obviously, a smart thing to do since Mormons had previously voted to acquit) is an important fact in this story that Bagley misses.

- Other than the unilateral ability to strike a limited number of jurors, neither party had control over the selection of the jury. According to press reports, the selection process was trilateral, with each side and the court having its say. It would be difficult to corrupt an entire jury pool for the twelve who would be empanelled. In any event, there was no limit to public and press contact with the jurors after the trial. After years of controversy over this case, as far as I know, no juror claimed to have been part of a conspiracy or to have received instructions from church authorities.

Judge and the deal?

- Bagley also cites Judge Boreman himself for evidence of a deal:

- The deal [Sumner Howard] struck with Brigham Young troubled even Howard. On the first day of the trial, the prosecutor stopped Judge Boreman as he was going to court. "Judge, I have eaten dirt & I have gone down out of sight in dirt & expect to eat more dirt." (p. 301)

- Boreman never believed Howard had made a deal, as I will show from correspondence discussed below. Nonetheless, the conversation quoted above says nothing of consequence. Boreman does not claim this to be evidence of any deal and even admits that another witness to the conversation denied it.118 Bagley tells us that Howard's disclosure troubled Boreman, but there is no evidence of this.

- Finally, Bagley tells us that "prevailing wisdom had it that the LDS church would dictate the outcome" and that one of Brigham Young's sons, John W. Young, took bets on the Chicago Board of Trade as to the outcome. Bagley's source for these two statements is the muckraking reporter John Beadle (p. 296). No serious scholar would accept as "prevailing wisdom" the conclusions of reporters for modern newspapers. Why should we accept John Beadle for "prevailing wisdom?" Admittedly, John W. Young may have been a colorful character, but I wouldn't rely on Beadle for the account of bets taken on the Chicago Board of Trade.

Evidence against the deal

- Evidence Refuting the Deal, Which Bagley Ignores. In the analysis above, we have seen that the U.S. district attorney would never have entered into a deal to thwart justice because he would have known it would have been unenforceable. We have also seen that Bagley's evidence of a deal is without foundation.

- Looking at the evidence refuting the notion of a deal, we find it is substantial. For years after the start of the Lee trial, until at least as late as 1884, federal prosecutors and investigators actively sought to bring other massacre participants to justice. Had the church and federal prosecutors struck a deal that only Lee would be prosecuted, we should expect that all parties to the deal would act thereafter in a manner consistent with a deal. None of the parties acted in such a manner.

- The Salt Lake Daily Tribune reports the church's call for continued prosecutions on 23 September 1876. A few days later and after Lee's conviction, the Tribune on 27 September 1876 published a summary of its grounds for believing that Howard had cut a deal with the church. One day after the Tribunes accusation, and most likely in response to the Tribunes charges, Howard described to the U.S. attorney general meetings with the church in which he lobbied for assistance in locating witnesses. "That aid was given." Howard also told the church authorities that he had no present evidence against them. Howard also complained of political intrigue from former prosecutors to malign his successful efforts.

- On 4 and 5 October 1876, U.S. District Attorney Howard wrote to U.S. Attorney General Alphonso Taft and explained his plans to arrest Haight, Higbee, and Stewart. Judge Boreman endorsed the 5 October letter with a note of his own (reproduced on p. 241) to Taft.

- The letter from Boreman to the U.S. attorney general shows several things that are fundamentally inconsistent with Bagley's theories about the deal. On the one hand, Bagley tells us that Boreman and Howard were troubled with the deal Howard had to make to thwart justice for other perpetrators (p. 301). On the other hand, the official correspondence shows that Boreman endorsed Howard's plan for further pursuit and arrest. Boreman agreed with Howard's progress. Under Bagley's view of the facts, Boreman should have called for Howard's ouster. It seems Bagley has this completely wrong.

- The evidence from official sources mounts against Bagley's and Brooks's theory of a deal. Taft authorized additional personnel to support Howard's and Boreman's request. U.S. Marshal William Nelson told Alphonso Taft on 19 December 1876 of the discovery of physical evidence in California, asking the Justice Department help to retrieve it. On 12 February 1877, Howard told Taft that Howard had located a possible eyewitness to the massacre, a Fancher child, now an adult languishing in the penitentiary for robbery. Howard asked Taft for help from the Justice Department to corroborate the witness's identity. The secretary of war responded with the information requested.

- On 23 February 1877, Boreman communicated to Howard a desire to spend more money on the marshal's efforts to intercept the other perpetrators before they fled to New Mexico. Howard and Nelson wrote to Taft on 3 March to urge that "the importance of availing ourselves of every reasonable means to bring others equally guilty to trial—is apparent. The trial of Lee has resulted in developments that give us a reasonable hope that the others—if arrested can be convicted."

- Taft's successor, Attorney General Charles Devens, responded to the correspondence of the third and questioned whether a five-hundred-dollar reward requested for the arrest of Haight, Higbee, and Stewart would be wasted. Lee was executed four days later on 23 March 1877.

- Three days after the execution, Howard recommended to Devens that undercover officers be used to effect the remaining arrests. On 2 May 1877, after learning that George C. Bates, Lee's former attorney, wished a special appointment to attempt the apprehension of Haight, Higbee, and Stewart, Howard complained to Devens that Bates's proposal was "another of Brigham Young's . . . games to thwart the officers" in their arrests. Why would Howard have condemned the "games" of Brigham Young to thwart further arrests if Howard had agreed, as Bagley and Brooks say, to forgo all arrests?

- On 20 October 1877, over one year after the deal Bagley claims the government made to thwart justice, Howard's assistant and Boreman petitioned the president of the United States for additional appropriations for a special agent.134 Howard wrote Devens, disagreeing with his assistant, asking that the money instead be spent on undercover agents who could approach the fugitives by stealth.

- After Howard resigned in February 1878 to pursue a respected career in law and politics in Michigan, federal efforts to arrest Haight, Higbee, and Stewart continued. Boreman wrote to Devens on 1 January 1879 with a request for additional appropriations. "The arrest of these men has been delayed so long that the people are not anticipating any effort in that way. This then would be a suitable time to make the arrests." Eleven months later, Devens approved the request. In 1884, or almost seven years after Bagley claims a deal was made to frustrate further prosecutions, an acting attorney general confirmed Utah inquiries from the U.S. marshal that reward money was still offered for the arrests of Haight, Higbee, and Stewart.

- Thus all of this post-Lee-conviction activity by the prosecutor's office and the judiciary would have made no sense whatsoever if all agreed and understood there was a deal to thwart justice. What is the answer from Young critics and Lee advocates on this point? Was it all a subterfuge involving two federal prosecutors, a federal judge, several U.S. marshals, a secretary of war, and at least three U.S. attorneys general?

Dwyer's work: Bagley's manipulation of source

- When Bagley gets to this postconviction official action, his analysis is stunted, missing nearly all the correspondence mentioned above. He relies solely on a doctoral dissertation by Rev. Robert Joseph Dwyer later published as The Gentile Comes to Utah: A Study in Religious and Social Conflict (1862—1890). This is a weak work, at least when it discusses post-Lee official action, because Dwyer lacked many of the official sources I have cited above. Nonetheless, with the limited sources Dwyer possessed, he does not conclude that a deal had been struck between prosecutors and the church.

- What annoyed me most about Bagley's use of Dwyer's work is that Bagley chose to cut and paste Dwyer's own words into Blood of the Prophets although Dwyer does not reach the same conclusions Bagley does. The dissonance in some of Dwyer's fuzzy logic becomes incomprehensible when Bagley repeats almost verbatim the Dwyer logic as original thought.

The Jailers and the Gilman Affidavit

- When Bagley does get specific with Dwyer's work, he focuses on a dispute between a claimed jailer, assistant U.S. Marshal Edwin Gilman, and U.S. District Attorney Sumner Howard (p. 308). Relying solely on Dwyer's secondary work, Bagley tells us that Gilman's affidavit reported that Howard at the trial intentionally suppressed Lee testimony that would have implicated Brigham Young. Bagley, however, does not refer to Gilman's affidavit because Dwyer lacks one and, hence, Bagley does not have it. After telling us about Gilman, Bagley reiterates the suggestion that "the Mormons had corrupted Howard" (p. 309).

- It is curious that when Bagley discusses the Gilman affidavit he relies on a secondary source that never had the affidavit. The affidavit in full, and Sumner Howard's response to the affidavit, were published in the New York Herald (James G. Bennett's paper) on 12 April 1877. The day before, the Salt Lake Daily Tribune had published Howard's response on 11 April.

- In his affidavit, Gilman declared that he was a jailer in Beaver. At Howard's request, Lee prepared a confession, and "as read to and by me, charged Brigham Young with direct complicity in the Mountain Meadows Massacre, as an accessory before the fact, that Brigham Young had written letters to Dame and Haight, at Parowan directing them to see that the emigrants were all put to death."

- Bagley, however, does not tell us about Howard's rebuttal to Gilman's charge. Howard's rebuttal seems irrefutable, and indeed, I am unaware that Gilman ever attempted a refutation of the rebuttal. Howard says that no Gilman affidavit was ever found at the Justice Department (the New York Herald reported it had been filed) and that Gilman disappeared so nobody could interview him. Howard said that Gilman was never a jailer at Beaver. Howard said that Gilman never had an opportunity to speak to Lee and thus Gilman would never have been in a position to hear any purported confession. Howard reported that "Gilman is a notorious liar; has been impeached here in Court, and there are not ten men in the Territory acquainted with him who would take his oath or word." Further, the "confession of Lee has not been sold, altered, suppressed or in any other manner put to an improper use." Because the Gilman affair is Bagley's chief source for a "deal," I find it remarkable that he does not even possess a copy of the Gilman affidavit.

A better account

- A more accurate account of the relationship between Howard and the jailers can be seen from an earlier 21 March 1877 article in the New York Herald that reported that the jailers were upset that Lee refused to implicate his accomplices. Howard had given up trying to get information "as was expected and as he indirectly promised." Nowhere is there any shred of evidence that Lee told Howard something that was not published in these newspapers. Nowhere is Gilman mentioned in the earlier article. Nowhere do we read any corroboration of the statements contained in the supposed Gilman affidavit. Justice of the peace and jailer Benjamin Spear had claimed one month earlier that Judge Boreman and other fellow officers were either timid or bribed by "Brigham Young's blood stained coin." Spear claimed obliquely that John D. Lee had more to say and had so told Spear at one time, but Spear wouldn't get specific about his charges. Spear also complained that John D. Lee was permitted to cohabit with his wives.

- U.S. Attorney General Devens asked Howard to come to Washington to explain the jailers' charges, specifically focusing only on a charge that the jailers were selling a confession for profit. Nowhere in Devens's letter does Devens give any credence to Gilman's or Spears's vague claims that Howard suppressed evidence that implicated Brigham Young. Devens would have mentioned such an incendiary charge had there been any credibility to it. On 16 April 1877, Howard told Devens that "I will state here that the allegations of Gilman are cruel wicked and infamous—without the least grain of truth." Bagley tells us that Howard went to Washington to respond to the charges against him, but the official correspondence shows that Devens accepted Howard's explanation and reversed his request to see Howard.

Summary of charges of a deal

- To summarize, the official correspondence shows years of prosecutorial effort to apprehend massacre perpetrators. This effort overwhelms the meager and faulty story Bagley puts together from the Gilman affair. To rely upon secondary material for the "deal" theory, particularly where primary material was published in the national press, is not good scholarship. Bagley's lack of knowledge of the official correspondence discussing prosecutorial effort is a significant impediment to his credibility.

An alternate view

- What really happened between Howard and the Church? Let me suggest a plausible explanation for the facts that have led laypersons in the past to think there was a deal to make Lee a scapegoat. After the first trial failed and Sumner Howard replaced the prior prosecutors, the Salt Lake Daily Tribune peppered its editorial column with charges of prosecutorial bungling. The paper charged the prosecutors with grandstanding against church authorities and failing to adduce specific evidence against Lee. U.S. District Attorney Howard, not willing to repeat the mistakes of his predecessors, decided he needed a different strategy and slate of witnesses. However, many of the desired witnesses could not be found. Howard met with church officials to lobby their support to encourage witnesses to come forward. Howard assured church authorities that he sought only justice and that he had no evidence against Brigham Young or George A. Smith. Nor did Howard give up on Brigham Young; both Orson F. Whitney and the New York Herald reported that Howard offered Lee a full pardon in exchange for evidence against Brigham Young. Church authorities probably got the word out to witnesses to encourage them to cooperate.

- Few of the witnesses in the first trial testified in the second. Howard did not call Klingensmith, who had turned state's evidence in the previous trial. This indicates to me that Howard did not want to repeat the errors of his predecessors. Howard probably asked the church to have a nominal presence at the trial. Daniel Wells agreed to testify, and he did so. Ostensibly, Wells's testimony was necessary to show that Lee was not a high church authority. The night before his testimony, Wells preached a fiery sermon in Parowan demanding justice, but not necessarily against Lee. (I have not seen the text of that sermon.) The Deseret News also published editorials demanding justice. The jurors deliberated. According to the Corry affidavit, the decision was not an easy one to make. No external force influenced the jurors, other than the social difficulty of convicting one's own. But, in the end, Lee was convicted. Investigations continued against other perpetrators, but they secreted themselves effectively in the wilds of the desert. No doubt the other perpetrators had plenty of Mormon friends and family willing to assist with their evasion.

Source(s) of the criticism

Critical sources |

- Will Bagley, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), 217–235.

- David L. Bigler, Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847–1896 (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1998), 243–252. (bias and errors) Review

- Sally Denton, American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, (Secker & Warburg, 2003), 209.

|

Did Brigham Young or the Church interfere with the trial of John D. Lee?

Prosecutorial misconduct was likely responsible for the failure of the first trial

Critics charge that the institutional Church interfered with the first trial of John D. Lee and others to prevent convictions in 1875-1876. [11]

Prosecutorial misconduct was likely responsible for the failure of the first trial. Lee was not tied to any criminal conduct, and prosecutors' desire to blame Brigham Young—without evidence—for the massacre led to the trial's failure.

One reviewer described the difficulties with this theory:

Second hand evidence

Blood of the Prophets argues that the church was guilty of obstructing the prosecution of the 1875 and 1876 trials of John D. Lee. Yet Bagley errs in his analysis of the events of the trials. He fails, with a few exceptions for the first trial only, to rely upon the actual transcripts. Instead, he relies upon exposés. These secondhand accounts are not accurate and have serious errors of omission and editorial addition. In particular, I object to Bagley's reliance upon William Bishop's Mormonism Unveiled for the second trial. Bishop's stenographer dropped and changed testimony in places. Abraham Lincoln's biographers have recognized the difficulty of using press accounts as they reconstructed the accessory-after-the-fact trial of Dr. Samuel Mudd, the physician who set John Wilkes Booth's leg. In contrast to Bagley, neither Brooks nor Leonard Arrington relied on press accounts for their analyses of the Lee trial. [12]

Blood of the Prophets also relies on the memoirs of Judge Jacob Boreman for his impressions of the trial. Except for perhaps the demeanor of witnesses, a judge's observations of witnesses could not add anything to the official transcript. Boreman's reminiscences demonstrate some real problems. With not a shred of evidence other than the speculation circulated by others, Boreman said he believed that high Mormon officials communicated death threats to witnesses of the massacre and that ordinary members of the church believed they were authorized to commit perjury by reason of the vows they took in the church's Endowment House. None of that is reflected in the trial transcript. Arrington opined that Boreman was prepared to believe the worst about the Mormons and that his naïveté made him clay in the hands of other federal anti-Mormon fanatics.

1875 trial

Turning to the events of the first trial in 1875, there is no evidence that the church obstructed justice. This trial mistried with a hung jury, to the universal denunciation of the church in the non-Mormon press. All Mormon jurors and one "backslider" voted to acquit. Three non-Mormons voted to convict (p. 296). Not a single witness tied Lee to any criminal activity, including former Mormon Bishop Philip Klingensmith, who turned state's evidence. The prosecutors, William C. Carey and Robert Baskin, used the trial to grandstand against Brigham Young. Even the [generally anti-Mormon] Salt Lake Daily Tribune admitted that the trial failure resulted from the prosecutors' "utter neglect of the business" and "disgraceful lethargy." [end of cited material]

Did Brigham Young order the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

There is substantial evidence that Brigham Young did not order the massacre. Will Bagley (and, following him, the author of One Nation Under Gods) have distorted the contents of the Huntington diary and ignored other evidence.

ONUG makes two related claims:

- Brigham Young ordered the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

- The Dimick Huntington diary entry proves that Brigham offered the natives cattle to carry out the massacre.

Both of these claims are false.

Responding to Bagley (and ONUG)

The book's argument is essentially identical (if less detailed) to Will Bagley's Blood of the Prophets. Bagley's analysis has been savaged by multiple reviewers. (See "Further Reading" in main article on Mountain Meadows Massacre.)

Wrote attorney Robert Crockett of Bagley's argument:[13]

- Bagley's "troubling new evidence," [which the author uses though he does not cite Bagley, since Bagley's book came out after the ONUG hardback edition] which separates his work from Juanita Brooks's, is simply a diary entry, dated 1 September 1857, in which Indian interpreter Dimick Huntington describes a meeting purportedly held between himself, Brigham Young, and twelve Indian chiefs:

- Kanosh the Pahvant Chief[,] Ammon & wife (Walkers Brother) & 11 Pahvants came into see B & D & find out about the soldiers. Tutseygubbit a Piede chief over 6 Piedes Bands Youngwuols another Piede chief & I gave them all the cattle that had gone to Cal[.] the southa rout[.] it made them open their eyes[.] they sayed that you have told us not to steal[.] so I have but now they have come to fight us & you for when they kill us then they will kill you[.] they sayed the[y] was afraid to fight the Americans & so would raise grain & we might fight.[14] (cf. p. 114)

- For Bagley this cryptic entry proves that "the atrocity was not a tragedy but a premeditated criminal act initiated in Great Salt Lake City" (p. 378). Blood of the Prophets tells us that "if any court in the American West (excepting, of course, one of Utah's probate courts) had seen the evidence [the Dimick Huntington diary] contained, the only debate among the jurors would have been when, where, and how high to hang Brigham Young" (p. 425 n. 42).

- This scrap of evidence cannot support Bagley's conclusions, particularly in light of contemporaneous evidence. Brigham Young, if it was truly he who spoke,[15] did not refer to a specific emigrant train. Instead, on that day and on many others, as I will demonstrate, he asked Indian tribal leaders to help scatter the cattle of the army and of all emigrants on the trail in front of the army in order to completely close the trail. As historian Norman Furniss observed fifty years ago, "early in the war at least, the Church's leaders had a deliberate policy of seeking military assistance from the Indians."[16] When Brigham Young told the Indian tribes he wanted assistance in fighting the Americans, he meant only the army.[17]

- Bagley tells us that the language in Huntington's diary entry for 1 September 1857 implies an instruction for attack on the Fancher train. Why then did Dimick Huntington use the same language elsewhere with Indian tribal leaders who could have had no geographic proximity to the Fancher train? For instance, two days earlier in Huntington's diary, 30 August 1857, Huntington wrote:

- I [Huntington] told them that the Lord had come out of his Hiding place & they had to commence their work[.] I gave them all the Beef cattle & horses that was on the Road to CalAfornia[,] the North Rout[,] that they must put them into the mountains & not kill any thing as Long as they can help it but when they do Kill[,] take the old ones & not kill the cows or young ones.[18]

- When Huntington talks about not killing anything "as Long as they can help it" he is talking about "cows." He asked the northern Indians for help to run cattle off the northern California route upon which the Fancher train would never tread. Following the massacre, Indian agent Garland Hurt—certainly no friend of the Mormons—noted the same requests were made to the northern Snake Indians.[19] T. B. H. Stenhouse also confirms that running the cattle off was a general strategy used successfully against the army.[20] Thus, Brigham Young's 1 September 1857 comment: "I gave them all the cattle" can only mean one thing. He offered the Indians all the cattle they could scatter that were owned by the army.