FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Summary: In September 1857 a group of Mormons in southern Utah killed all adult members of an Arkansas wagon train that was headed for California. Critics charge that the massacre was typical of Mormon "culture of violence," and claim that Church leaders—possibly as high as Brigham Young—approved of, or even ordered the killing.

Jump to details:

Henry B. Eyring:

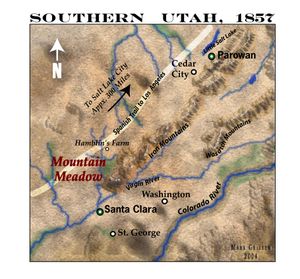

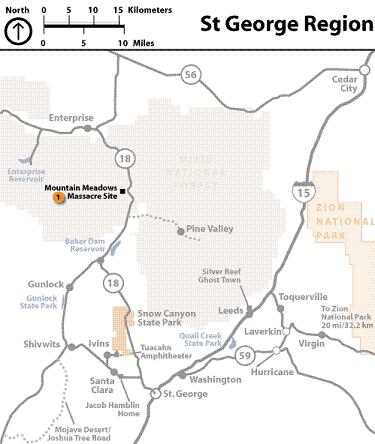

On September 11, 1857, some 50 to 60 local militiamen in southern Utah, aided by some American indian[s], massacred about 120 emigrants who were traveling by wagon to California. The horrific crime, which spared only 17 children age six and under, occurred in a highland valley called the Mountain Meadows, roughly 35 miles southwest of Cedar City. The victims, most of them from Arkansas, were on their way to California with dreams of a bright future“ (Richard E. Turley Jr., ”The Mountain Meadows Massacre,“ Ensign, Sept. 2007).

What was done here long ago by members of our Church represents a terrible and inexcusable departure from Christian teaching and conduct. We cannot change what happened, but we can remember and honor those who were killed here.

We express profound regret for the massacre carried out in this valley 150 years ago today and for the undue and untold suffering experienced by the victims then and by their relatives to the present time.

A separate expression of regret is owed to the Paiute people who have unjustly borne for too long the principal blame for what occurred during the massacre. Although the extent of their involvement is disputed, it is believed they would not have participated without the direction and stimulus provided by local Church leaders and members. [1]

Overview |

In September 1857 a group of Mormons in southern Utah killed all adult members of an Arkansas wagon train that was headed for California. Critics charge that the massacre was typical of Mormon "culture of violence," and claim that Church leaders—possibly as high as Brigham Young—approved of, or even ordered the killing.

One of the most tragic and disturbing events in Mormon history took place on 11 September 1857, when approximately 120 men, women and children, traveling through Utah to California were massacred by a force consisting of Mormon militia members and Southern Paiute Indians. The Mountain Meadow Massacre, as it is known, has remained a topic of interest and controversy as Mormons and historians struggle to understand this event, and the Church's detractors seek to exploit it for polemical purposes.

Shortly before July 24th, 1847, the first party of Mormon pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley. These Saints were the first vanguard of Church members who had been driven from Nauvoo, Illinois, by angry mobs. At the time of its first settlement, the area that came to be known as Utah still belonged to Mexico, but was ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo following the end of the Mexican-American War in early 1848. (The treaty ceded all of what would become California, Nevada, and Utah, as well as parts of modern-day Texas, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming.)

Over the next two years the bulk of the Church members who had been driven from Nauvoo reached the valley. Great Salt Lake City was built, and under Brigham Young's direction satellite settlements were established north, south, and west of the city. The sites for these settlements were often chosen because of proximity to an important natural resource; one such resource was the iron ore deposits found in what became known as Iron County in Southern Utah.

The continuation of successful missionary work in the Eastern United States and Europe brought a steady influx of Mormon converts to the Mormon communities; the population continued to grow, and settlement expanded outward into present-day Idaho, Canada, Nevada, California, Arizona, Wyoming, and Northern Mexico.

In 1850, Utah was established as a U.S. territory, with Brigham Young as its first governor. Because of its territorial status, the federal government retained the right to appoint officials at various levels, in addition to actual federal offices existing within the territory. While there were, no doubt, many honest public servants among them, a number of the federal appointees to both territorial and federal positions, including some judges, turned out to be both morally venal and abusive of the prerogatives of their offices. Scandals arose over the behavior of some of these men, who left the territory in disgrace. Rather than accepting responsibility for their own failures, a group of them, upon returning to the East, published claims that they had been forcibly expelled, and that the Mormons were rebelling against federal authority.

These claims caused quite an uproar in Washington, where the nascent Republican Party demanded something be done about the Mormons. Acting without benefit of an investigation, U.S. President James Buchanan appointed Alfred Cumming as territorial governor and, on June 29, 1857, ordered federal troops to escort Cumming to Utah. Additionally, Buchanan ordered the cessation of all mail service to Utah in an effort to provide the advantage of surprise for the advancing troops.

Despite the efforts of Buchanan to keep the advance of the army secret, Mormon mail runners notified Brigham Young, the incumbent territorial governor, the very next month that troops were travelling to Utah. He had not been officially notified that he was to be replaced, so he viewed the news—combined with the efforts to hide the movement of the troops—as an act of war by the United States government against the Mormons. Brigham closed all Church missions, instructing all missionaries to return to Utah, and ordered the abandonment of the more isolated Mormon colonies. He prepared to defend the territory against the approaching army by adopting a "scorched earth" policy. He sent small parties to harass the approaching troops with the intent of slowing their progress while he prepared the Saints for the plausible possibility of battles with U.S. troops.

The news of the approaching army spread quickly through the body of the Saints as preparations were made. Many Mormon settlers vividly remembered the hardships of being forcibly (and violently) expelled from Missouri and Illinois, and were resolved not to be driven from their homes again. The mood in the territory was grim and determined. This conflict, known as the Utah War, was ultimately resolved peacefully; but it was into this tense atmosphere the Baker-Fancher train entered in August of 1857.

The Baker-Fancher train consisted of California-bound emigrants, men women and children, who started their journey in Arkansas and Missouri. The exact number of people in the train is estimated at 120, but some reports have put it as high as 140. Led by John T. Baker and Alexander Fancher, the train was reported to have been well-stocked, with plenty of cattle, horses, and mules.

The Baker-Fancher train arrived in Salt Lake City about the end of July 1857, camping west and a little south of the city on the Jordan River. Their arrival did not appear to raise any eyebrows or concerns, as there was no mention of them in the newspapers of the time. The group was advised by Elder Charles C. Rich of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to head toward California by circling around the northern edge of the Great Salt Lake, and they began in that direction. Upon travelling as far as the Bear River, the train decided to take the southern route. This caused them to pass through Salt Lake City again, moving further south through Provo, Springville, and Payson.

There were no reports of problems related to the Baker-Fancher party until they reached Fillmore, about 150 miles south of Salt Lake City. Commencing at this point and through settlements to the south, there were complaints that the emigrants boasted of participating the violence against Mormons in both Missouri and Illinois, that they poisoned a spring, and that they threatened to destroy one of the Mormon settlements.

It was also common knowledge that the train originated in Arkansas, where earlier in the year beloved apostle Parley P. Pratt had been murdered near the town of Van Buren. Rumor had it some of the members of the train were among those who had participated in Pratt's murder, or that they bragged about his killing. There are also reports that some of the emigrants told a few Latter-day Saints that once they had transported their families to California they would return, join the army, and help subdue the Mormons.

Whether there is any truth to these rumors, it is clear the travels of the Baker-Fancher train through southern Utah did not go unnoticed as they were in northern Utah. The presence of the train seemed to exacerbate the tensions already present due to the Utah War.

Commencing with the opening of Oregon Territory, and accelerated by the discovery of gold in California, large numbers of emigrants crossed the interior of the continent to the West Coast. Before the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869, overland travel was both difficult and dangerous. Native Americans, alarmed by the ever-increasing numbers of white settlers crossing their land, frequently attacked emigrant groups. Weather was another potential danger, with winter coming early to the high country and sudden storms occurring during all seasons of the year. For protection against these hazards, emigrants typically banded together in large parties called "wagon trains," covered wagons of the "prairie schooner" type being the most typical vehicles used. The climate made overland travel a seasonal affair as emigrant parties would try to complete their crossings during the warm months. To be caught on the high plains or the mountain passes when winter came was often a deadly mistake.

The Mormon settlements of Utah provided important rest and reprovisioning points for overland travelers. One of the most widely used wagon trails to California branched off the Oregon trail in Northern Utah, running almost due South through Salt Lake City, eventually joining the Old Spanish Trail. Emigrants could purchase foodstuffs and other supplies from businesses in Salt Lake City and other towns, while their animals—both beasts of burden and any livestock—could find excellent grazing at a spot near the west end of the Pine Valley Mountains, about 30 miles west of Cedar City and 28 miles north of St. George, known as las Vegas de Santa Clara or the Mountain Meadows. It was common for emigrant parties to camp there for several days or even weeks while their animals gained condition for the grueling desert crossings still to come.

There were many participants in the tragedy at Mountain Meadows. The following are considered to be the main participants, from a historical perspective. (The individuals are listed in alphabetical order.)

William H. Dame was, at the time of the massacre, the commander of the Iron Military District with the militia rank of colonel. He was also serving as president of the Parowan Stake. Initially, he counseled letting the wagon train leave in peace. Later, he decided not to help the emigrants fend off what he thought was an Indian attack unless they requested it. Finally, becoming aware of the true situation at the Mountain Meadows, he reluctantly authorized the use of the militia to finish the massacre in time to avoid discovery. While not at the site until after the massacre, he was, by the standards of military justice applicable both then and now, administratively responsible for the actions of officers and soldiers under his command.

Isaac C. Haight was a major over the Second Battalion in the Iron County militia and president of the Cedar City stake. Haight was the mastermind behind the massacre. After being denied permission to use the militia, Haight recruited John D. Lee and others to incite the Indians to attack the train. Efforts to bring Haight and others to justice after the massacre proved to be fruitless.

John H. Higbee was a major over the Third Battalion in the Iron County militia and town marshal of Cedar City. His ecclesiastical position was first counselor in the stake presidency of Isaac C. Haight. After a failed attempt to arrest rowdy members of the train for criminal offenses, he conspired with Haight to punish the wagon train. When Dame permitted, Higbee led troops to the Meadows carrying orders to completely destroy the wagon train.

Philip Klingensmith was a bishop in Cedar City and private in the Iron County militia. In this latter role, he carried orders and other messages between various militia officers. He was present at the massacre and subsequently turned states' evidence, but his testimony was of no real help to the authorities.

John Doyle Lee was a major over the Fourth Battalion in the Iron County militia. At the Mountain Meadows, Lee led Indians and other Mormons in the early unsuccessful stages of the siege. After Higbee's arrival with reinforcements, Lee convinced the emigrants to surrender their weapons under false pretenses. Lee was the only person ever brought to trial for his involvement in the massacre.

As the Baker-Fancher train camped at Mountain Meadows, some of the residents of Cedar City and the surrounding areas determined that some action needed to be taken against the emigrants. The heightened anxiety brought on by rumors swirling about the train, the advancing federal troops, the drought that many had suffered through for the year, and the memories of violence in Missouri and Illinois all combined in an explosive atmosphere; yet the residents were unclear on what action they should take.

This excellent summary of events in the days immediately preceding the massacre is provided by Robert H. Briggs:

In a meeting at Cedar City on the afternoon of September 6, 1857, local leaders received word the wagon train at Mountain Meadows had been surrounded by Paiute Indians who were determined to attack the emigrants. (Some historians are undecided as to whether Paiute Indians were actually involved in the massacre at all; some assert that it was white men disguised as Indians.) The leaders decided that they needed to ask Brigham Young what to do, so they dispatched a fast rider to Salt Lake City with a message to that effect. James H. Haslam, the messenger, left on Monday, September 7, and made the 300-mile journey in just a little more than three days. Within an hour he had an answer from Brigham Young and began the journey back to Cedar City. Young's message said, in part, "In regard to the emigration trains passing through our settlements, we must not interfere with them until they are first notified to keep away. You must not meddle with them. The Indians we expect will do as they please but you should try and preserve good feelings with them." Unfortunately, the messenger arrived back in Cedar City two days after the massacre, on September 13, 1857.

As Haslam was leaving for Salt Lake City on September 7, the Indians' attack commenced. Several of the emigrants were killed, as were several of the Indians, producing a stalemate situation. The emigrants circled their wagons and dug into a rifle pit and the Indians sent a call to the surrounding country for reinforcements. They also sent for John D. Lee, an area farmer on friendly terms with the Indians. According to Lee's later court testimony, the Indians asked him to help with the attack. Lee instead sent word to Cedar City on September 10, asking what should be done.

It is at this point that the exact nature of the events becomes unclear; most details being provided by Lee, and the veracity of his testimony is naturally suspect. He indicated that in short order there were quite a few other Indians and white settlers who had joined the group outside of the siege. The night of September 10 and the following morning the whites debated what to do. It appears that one incident which factored into their eventual murderous decision was the killing, the night before, of one of the emigrants by white men. It appears that two men from the Baker-Fancher party left the camp, evaded those surrounding their camp, and started toward Cedar City to request help. Within a few miles the two met three white men, whom they asked for help, but then they were attacked by the white men. One of the two was killed, and the other was able to make his way back to the Baker-Fancher party.

How could such news factor into the decision to massacre the emigrants? There is no doubt the news that both Indians and white men—Mormons—were attacking the emigrants was not well received. If any of the emigrants should escape to California and tell the story, prejudice against the Mormons—already quite high—would be incited and there would be greater likelihood that a military force would move upon the southern settlements from the west. Facing down an army from the east might be bearable, but facing one from both the east and the west could seem unbearable.

Such reasoning does not excuse the decision the white men in the area made; it is only mentioned as a factor in understanding some of the excitement and the hysteria enveloping those in the area. The decision was apparently made on the morning of September 11 to destroy all in the Baker-Fancher party over the age of seven. To effect the massacre with a minimum of loss among the white men, it was decided to lure the emigrants out of their circled wagons and into the open. In the words of B.H. Roberts,

Thus it was that on September 11, a flag of truce was carried to the Baker-Fancher party by William Bateman. He was met outside the camp by one of the emigrants, a Mr. Hamilton, and an arrangement was made for John D. Lee to speak to the emigrants. Lee described to them a plan to get them through the hostile Indians. The plan involved the emigrants giving up their arms, loading the wounded into wagons, and then being followed by the women and the older children, with the men bring up the rear of the company in single-file order. In return for compliance with these terms, the white men would give the emigrants safe conduct back to Cedar City where they would be protected until they could continue their journey to California.

The emigrants agreed, the wagons were brought forward and loaded with the wounded and the weapons, and the procession started toward Cedar City. Within a short distance, one armed white man was positioned near each of the Baker-Fancher party adults, ostensibly for protection. When all was in place, a pre-determined signal was given and each of the armed white men turned, shot, and killed each of the unarmed Baker-Fancher party members. Within three to five minutes the entire massacre of men, women, and older children was complete. The only members of the original party remaining were those children judged to be under eight years old, numbering about 17 persons.

After the massacre, local leaders attempted to portray the killings as solely the act of Indians. This effort began almost immediately, with John D. Lee's report to Brigham Young. It wasn't long, however, before charges started to surface that Indians were not the only participants, but that there were whites involved. Responding to the charges that whites were involved, Brigham Young urged Governor Cumming to investigate the matter fully. However, the governor maintained that if whites were involved, they would be pardoned under the general amnesty granted by the governor to the Mormons in June 1858. This amnesty was issued at the behest of U.S. President James Buchanan, and covered all hostile acts against the United States by any persons in the course of the Utah War.

Most scholars recognize that there was a local cover-up of the massacre. What there is disagreement on is how involved higher Church leaders were in any cover-up. Some have concluded that Brigham Young, himself, was involved in a cover-up, but others argue that the evidence does not support such a conclusion. It is known that Brigham was not privy to the full details at first; he was told that only Indians were involved. In April 1894 Wilford Woodruff stated the following concerning the massacre and Brigham Young's supposed involvement:

Most historians have followed Juanita Brooks, who concluded that Brigham did not know about the massacre before-hand, and was horrified to learn of it.[5]

Of course, it wasn't just Indians who were involved. The best available evidence supports two levels of cover-up: (1) concerted denials of guilt by massacre participants, including attempts to shift the blame to their erstwhile Indian allies, and (2) attempts by Mormons not involved in the massacre to shield accused persons from capture or prosecution. The latter actions did not normally arise out of any approval for the massacre, and indeed were usually undertaken without knowledge of the guilt of the persons being shielded; rather they reflected a feeling of community solidarity versus the coercive power of an often-hostile government, and a pervasive mistrust of U.S. authorities and their willingness or ability to ensure that Mormon defendants would receive a fair trial. Accusations of any more substantial cover-up, either by the Mormon Church as an institution, or by its highest leaders, are not supported by the available evidence. </onlyinclude>

Overview |

Eventually, as more information came to light, some of the principal participants were excommunicated from the Church. One participant, John D. Lee, was found guilty of murder in federal court after twenty years and two trials. The first trial occurred in 1875, before the anti-Mormon judge Jacob Boreman. The prosecutor was an even more notorious anti-Mormon named R. N. Baskin. This official failed to properly try the case against Lee, presented very little evidence against him, and instead focused upon an attempt to prove Brigham Young's complicity in the massacre. This trial ended with a hung jury.

Lee's second trial occurred the following year; the prosecutor was U.S. District Attorney Sumner Howard, and Boreman was again the presiding judge. This time around, the case was properly tried; the jury heard overwhelming evidence against Lee, who was duly convicted and sentenced to be executed for his crime. On March 23, 1877, Lee was executed at Mountain Meadows and buried in Panguitch, Utah. Though other Mormons were certainly as culpable as Lee (he did not act alone), he was the only one executed.

The long hiatus between the massacre and Lee's trial is one of the factors which some feel support the accusations of an institutional cover-up. However, the reasons for this delay suggest otherwise. As mentioned earlier, Governor Alfred Cumming believed the massacre was covered by the Utah Amnesty, thus making any investigation pointless. This belief was shared by a number of eminent legal authorities, including some charged with law enforcement in Utah. The attempts by some politically minded judges, such as John Cradlebaugh, to direct the investigation and prosecution of crime in Utah and conduct "crusades" against the Mormon Church actually hindered, rather than helped, prosecutorial and investigative efforts.

An additional claim sometimes put forward is that Lee was a "scapegoat," that some kind of corrupt agreement existed between Church leaders and territorial authorities to not pursue anyone else. However, the historical records do not back this up. After Lee's execution, territorial authorities wanted to continue the investigations with a view to bringing more of the guilty parties to justice. The official correspondence shows a reward was offered for the capture of Isaac C. Haight, William Stewart and John Higbee, all suspects in the planning and/or execution of the massacre, and that this reward remained on offer for at least seven years. Lee was not tried as a "scapegoat" but as an actual participant in the massacre, evidently the leading participant, who had done more than any other person to bring it about, and who had actually killed five people.

Almost as soon as news of the massacre reached the eastern United States, enemies of the Church began exploiting it for polemical purposes. The content of the various polemical accounts of the massacre varies considerably, but the intent of the accounts is always and everywhere the same: to explain the massacre as a consequence of the doctrine, beliefs, practices or culture of the Mormon Church, and thus destructive of its truth claims.

When writing about the Mountain Meadows Massacre in his Comprehensive History of the Church, B.H. Roberts stated that he

Most scholars and historians are quick to admit they don't have all the facts related to the massacre, and probably never will. That hasn't stopped some writers, for polemical reasons, from using a broad brush to denigrate the Church and its early leaders relative to the crimes of September 11, 1857.

There have been many accounts of the events surrounding the Mountain Meadows Massacre and a small library could be filled with pertinent materials. Perhaps the best-known of the recent polemical accounts are:

Certain themes continue to re-emerge in polemical accounts of the massacre. The claim that it was the worst massacre in American history is a common one; accusations of direct complicity on the part of Brigham Young, of subsequent institutional cover-up or of the "scapegoating" of John D. Lee, are common. Perhaps the following comments relative to Brigham Young's involvement may be instructive:

The events that transpired during the Mountain Meadows Massacre have rightfully lived in infamy; there is no explanation that can justify the murders of those five days in September, and we cannot fully understand them. In the words of one scholar, "the complete—the absolute—truth of the affair can probably never be evaluated by any human being; attempts to understand the forces which culminated in it and those which were set into motion by it are all very inadequate at best."[3]

In spite of the tragedy, efforts have been made to heal the wounds gouged into the collective American psyche 150 years ago. In the 1980s descendants of the victims and the perpetrators met together to start bridging the divide and make peace with the past. In a series of meetings, the seeds of trust were planted and a hopeful sense of accord started to bloom. On September 15, 1990, many of these descendants gathered together at Mountain Meadows to dedicate a memorial and marker to those who died there. The new memorial was a rendition of the original rock cairn constructed at the site by a military expedition under the direction of Major James H. Carleton about two years after the massacre.

Nothing can excuse the actions of those who perpetuated the Mountain Meadows Massacre. It may be possible, however, to better understand how basically good, law-abiding people (both before and after the massacre) could have been induced to carry out the massacre's actions.

Researchers have described a "culture of honor" which prevailed in the American South both before and after the Civil War, and illustrate how real or perceived insults or threats from the Fancher party might have moved some to violence:[4]

(Note that the false belief that the Fancher party was guilty of poisoning water supplies could have stirred the same worries in the LDS settlers.)

(Note that LDS settlers in southern Utah were in a similar setting, depending on a similar economic model. They were, furthermore, threatened by the coming U.S. Army).

The threat to honor would have been particularly profound if the Mormons believed that their plural wives were being offended or insulted by being called "whores" by the immigrant party:

With their history of being repeatedly driven, at least Mormon settlers were surely afraid of appearing weak and vulnerable, which would invite further attacks. That they were weak and vulnerable to the approaching federal army would have only made matters worse.

We emphasize that this does not excuse the massacre, but it makes the decisions and actions of those involved perhaps more explicable.

“On September 11, 1857, some 50 to 60 local militiamen in southern Utah, aided by some American indian[s], massacred about 120 emigrants who were traveling by wagon to California. The horrific crime, which spared only 17 children age six and under, occurred in a highland valley called the Mountain Meadows, roughly 35 miles southwest of Cedar City. The victims, most of them from Arkansas, were on their way to California with dreams of a bright future“ (Richard E. Turley Jr., ”The Mountain Meadows Massacre,“ Ensign, Sept. 2007).

“What was done here long ago by members of our Church represents a terrible and inexcusable departure from Christian teaching and conduct. We cannot change what happened, but we can remember and honor those who were killed here.

“We express profound regret for the massacre carried out in this valley 150 years ago today and for the undue and untold suffering experienced by the victims then and by their relatives to the present time.

“A separate expression of regret is owed to the Paiute people who have unjustly borne for too long the principal blame for what occurred during the massacre. Although the extent of their involvement is disputed, it is believed they would not have participated without the direction and stimulus provided by local Church leaders and members” (Henry B. Eyring, in “Expressing Regrets for 1857 Massacre,” Church News, Sept. 15, 2007).

Critical sources |

|

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now