FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Critics of Mormonism allege that the Manifesto ending the practice of polygamy, printed as Official Declaration 1 in the LDS scriptures, was not the product of revelation but rather of legal pressure from the U.S. government, or alternately, of a compromise to achieve statehood. Critics also point to some marriages contracted after the Manifesto as evidence for their claims.

There was great political, legal, and even military pressure brought against the Saints because of plural marriage. The members endured great privations for their faith.[1]

Wilford Woodruff was clear that the Lord had made it his "duty" to issue the Manifesto. It is impossible to know what President Woodruff "really" thought about what he was doing. But, he insisted and the other Church leaders insisted that he had been guided by the Lord in the decisions made during this difficult period.

His decision also has clear Biblical parallels for peoples in similarly oppressive political circumstances.

This event has a parallel in the book of Jeremiah. The Torah instructs the Israelites to remain an independent people and to not make contracts or treaties with the surrounding nations. Many Jews in Jeremiah's day likely saw that instruction as further reason to rebel against their vassal-state condition as a subject of Babylon.[citation needed] Jeremiah, however, told them they should submit to their present political condition. He particularly warned them that if they disobeyed, they would lose their freedom and the temple. Choosing to heed their own interpretation of a dead prophet's word rather than obey the living prophet, the Jews did not submit to Babylonian rule and lost their lands, possessions, and access to the holy temple.

This outcome is very similar to what Wilford Woodruff saw in vision.

The Lord showed me by vision and revelation exactly what would take place if we did not stop this practice. If we had not stopped it, you would have had no use for . . . any of the men in this temple at Logan; for all ordinances would be stopped throughout the land of Zion. Confusion would reign throughout Israel, and many men would be made prisoners. This trouble would have come upon the whole Church, and we should have been compelled to stop the practice. Now, the question is, whether it should be stopped in this manner, or in the way the Lord has manifested to us, and leave our Prophets and Apostles and fathers free men, and the temples in the hands of the people, so that the dead may be redeemed. . . . I say to you that that is exactly the condition we as a people would have been in had we not taken the course we have. OD—1 off-site

The Edmunds-Tucker Act granted the federal government unprecedented powers in prosecuting Mormon polygamists, and prosecutors took these powers to cruel and illegal extremes:

In the Edmunds-Tucker Act, [Congress] provided that a wife was a competent witness in polygamy, bigamy, and cohabitation trials and required that records be kept of weddings in the territories. These provisions still retained one restraint on spousal testimony, however; they provided only that a willing wife would be allowed to testify. The act specifically forbade attempts by the judiciary to compel wives to testify against their husbands. Utah’s judges did not always follow the law, however. A number of Mormon women were required to testify against their husbands or face contempt charges. The power of contempt could be a fearful weapon. On the basis of the most sketchy or nonexistent hearings, Mormon wives who refused to testify against their husbands could be sent to prison for indefinite periods. In 1888 Representative Burnes read to the House of Representatives a report by a visitor to Utah’s prison:

"I found in one cell (meaning a cell of the penitentiary in Utah) 10 by 13 1/2 feet, without a floor, six women, three of whom had babies under six months of age, who were incarcerated for contempt of court in refusing to acknowledge the paternity of their children. When I plead with them to answer the court and be released, they said: "If we do, there are many wives and children to suffer the loss of a father."[2]

The most reprehensible aspect of this treatment of the women is that it was completely unnecessary. With the evisceration of evidentiary standards, the courts were practically assured of convictions without the testimony of Mormon wives:

In retrospect it is difficult to offer any explanation for this judicial conduct toward Mormon wives other than a spirit of vindictiveness. The polygamy laws, which were being vigorously enforced in the latter part of the 1880s, imposed ample punishment for the women who stubbornly clung to polygamy. The imposition of contempt sentences on wives who refused to testify introduced a sort of random sexual equality in the federal punishment of polygamy that was being imposed on Utah’s Mormons. Courts had reduced the quantum of evidence required to establish polygamy or cohabitation to such a low level that in almost any case ample alternate sources of proof must have been available. So Utah’s courts could not have believed that they needed to compel Mormon women to testify in order to convict their polygamous husbands. The cohabitation cases produced heartrending stories of suffering and pathos. Men were forbidden to associate with their children or provide for their former wives. Women were denied care and association with former husbands. Moreover, the law, not limited to prohibiting future polygamous marriages, fell with all its severity upon people whose relationships had most often been established when the law did not unambiguously forbid them.[3]

Legal challenges brought against Edmunds-Tucker failed, removing the final obstacle to those who sought to use the law to not simply stop polygamy, but to destroy the Church:

Congress, the Presidency, and the Supreme Court combined to generate repressive legislation and distortions of Constitutional jurisprudence which to this day are unequalled in the degree to which they destroyed individual and institutional rights, freedoms, and privileges. Politicians so successfully exploited the situation that at times the nation was prepared to accept the destruction of the Church and its members.[4]

President Woodruff attended a council meeting on 24 September 1890, and presented a statement which he had written, declaring: "I have been struggling all night with the Lord about what should be done under the existing circumstances of the Church. And here is the result."[5]

This document was to become the Manifesto. After the Manifesto was revised by the First Presidency, three members of the Quorum of the Twelve, and a few others, it was sent to the media.

Of the process, George Q. Cannon wrote:

This whole matter has been at President Woodruff’s own instance. He has felt strongly impelled to do what he has, and he has spoken with great plainness to the brethren in regard to the necessity of something of this kind being done. He has stated that the Lord had made it plain to him that this was his duty, and he felt perfectly clear in his mind that it was the right thing.[6]

President Cannon also spoke soon after the Manifesto's publication, and indicated that President Woodruff’s writing of the Manifesto had been done "under the influence of the ‘Spirit’" and promised that "when God speaks and…makes known His mind and will, I hope that I and all Latter-day Saints will bow in submission to it."[7] Thus, the Manifesto was considered to be a divinely mandated and inspired step by leaders at the time.

Some wonder whether or not Wilford Woodruff was actually inspired to end polygamy.

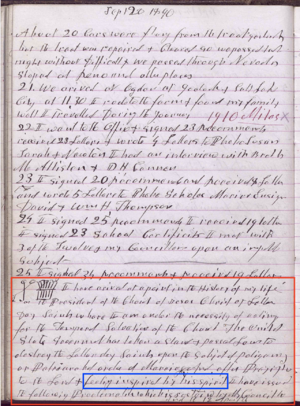

Woodruff wrote in his journal on September 25, 1890 that "I have arived at a point in the History of my life as the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints whare I am under the necessity of acting for the Temporal Salvation of the Church. The United State Governmet has taken a stand & passed Laws to destroy the Latter day Saints upon the subject of poligamy or Patriarchal order of Marriage. And after Praying to the Lord & feeling inspired by his spirit I have issued the following Proclamation which is sustaind by My Councillors and the 12 Apostles."

Thus, anyone denying that Woodruff had a revelation must either not believe in God, not believe in the Latter-day Saint God, or just believe that Woodruff was lying in the case of fundamentalists.

Some of these marriages were apparently sanctioned by some in positions of Church leadership.

Some Church members unfamiliar with the history behind the aggressive Federal anti-polygamy movement have been troubled by critics who try to portray Church members’ and leaders’ choices as dishonest and improper. It is important to realize that this is a point on which modern enemies of the Church would be impossible to satisfy. If the Church had acquiesced to government pressure and stopped polygamy completely in 1890, the Church would then be charged with having "revelations on demand," or with abandoning something they claimed was divine under government pressure. In fact, prior to the Manifesto, the attorney prosecuting Elder Lorenzo Snow for polygamy "predicted that if Snow and others were found guilty and sent to prison church leaders would find it convenient to have a revelation setting aside the commandment on polygamy."[8]

If they were to comply with the law, they would (in the eyes of some) be admitting that revelation came "on demand" and in response to secular pressure or "convenience." Their enemies would "win" no matter what they did.

But, this did not happen—the leaders and members of the Church were literally willing to do anything they were commanded to do, in order to obey the Lord, until they were told otherwise. Impressively, the Church and its leaders took the only possible course which would preserve its revelatory integrity: only when they literally had no further choice besides dissolution was the plural marriage commandment completely rescinded.

It should be remembered, finally, that a key doctrine of the Church is that no one should have to take anyone else’s word for something—"that man should not council his fellow man, neither trust in the arm of flesh—but that every man might speak in the name of God the Lord, even the savior of the world."(D&C 1꞉19-20.) This doesn’t apply to polygamy alone; every discussion of testimony includes it. Joseph Smith made numerous other claims that might make us skeptical: appearances of God and Jesus, angels, gold plates, and everything else. Said he:

Search the scriptures—search the revelations which we publish, and ask your Heavenly Father, in the name of His Son Jesus Christ, to manifest the truth unto you, and if you do it with an eye single to His glory nothing doubting, He will answer you by the power of His Holy Spirit. You will then know for yourselves and not for another. You will not then be dependent on man for the knowledge of God; nor will there be any room for speculation.[9]

As President Cannon explained, the leaders of the Church were not exempt from the rigors of receiving revelation:

Yet, though [Church doctrines] shocked the prejudices of mankind, and perhaps startled us as Latter-day Saints, when we sought God for a testimony concerning them, He never failed to give unto us His Holy Spirit, which witnessed unto our spirits that they were from God, and not of man. So it will be to the end. The Presidency of the Church have to walk just as you walk. They have to take steps just as you take steps. They have to depend upon the revelations of God as they come to them. They cannot see the end from the beginning, as the Lord does. They have their faith tested as you have your faith tested. So with the Twelve Apostles. All that we can do is to seek the mind and will of God, and when that comes to us, though it may come in contact [conflict?] with every feeling that we have previously entertained, we have no option but to take the step that God points out, and to trust to Him…[10]

The Doctrine and Covenants clearly indicates that the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve are of equal authority[11] and that every decision should be done in unanimity in order to make such decisions binding upon the Church[12]: to make them "official," as it were. Clearly, President Woodruff did not follow this practice—which would be very strange if he expected the Manifesto to be read as a formal revelation insisting that all polygamous practices immediately cease: only three of the apostles even saw the Manifesto prior to its publication. The leaders were agreed that President Woodruff had been right to issue it, and acknowledged his action of the Lord; the full implications of the Manifesto, however, were still the subject of discussion and debate.

President Woodruff did not frame the matter as a declaration from the First Presidency and the Twelve (which would be required for any official change in doctrine or practice). Rather, he spoke of the Manifesto as a "duty" on his part, which the Lord required. Even the wording of the Manifesto reflects this—it does not speak of "we the First Presidency and Council of the Twelve," but simply of Wilford Woodruff in the first person singular. The wording is careful and precise: "I hereby declare my intention to submit to those laws, and to use my influence with the members of the Church over which I preside to have them do likewise… And I now publicly declare that my advice to the Latter-day Saints is to refrain from contracting any marriage forbidden by the law of the land."(OD-1) Thus, President Woodruff announces a personal course of action, but does not commit other general authorities or the Church—he even issues "advice," rather than a "command" or "instruction." No other signatures or authorities are given, other than his own.

A useful comparison can be made with Official Declaration 2, which follows the prescribed pattern for Church government:

…the First Presidency announced that a revelation had been received by President Spencer W. Kimball…[who] has asked that I advise the conference that after he had received this revelation…he presented it to his counselors, who accepted it and approved it. It was then presented to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who unanimously approved it, and was subsequently presented to all other General Authorities, who likewise approved it unanimously.(OD-2)

Even at this meeting their intent was clear, since they debated whether the Church as a whole should sustain the Manifesto, since "some felt that the assent of the Presidency and Twelve to the matter was sufficient without committing the people by their votes to a policy which they might in the future wish to discard."[13]

It is evident that these united quorums did not consider the Manifesto to be a revelation forbidding all plural marriage in 1890: for, why would they then contemplate the Church wanting to "disregard" it? The leaders were doubtless still hoping that they might be able to gain some reprieve, and continue to practice their religion without civil or criminal penalty.

Perhaps most convincingly, an editorial in the Church’s Deseret News responded to the government’s Utah Commission, which had argued that President Woodruff needed to "have a revelation suspending polygamy." The editorial advised that "[w]hen President Woodruff receives anything from a Divine source for the Church over which he presides he will be sure to deliver the message."[14] This was written five days after the publication of the Manifesto. It seems clear that President Woodruff considered his action inspired and divinely directed; however, he and the Church did not believe that God had, by the Manifesto, told them to cease all plural marriage.

George Q. Cannon said,

But the nation has interposed and said, "Stop," and we shall bow in submission, leaving the consequences with God. We shall do the best we can; but when it comes in contact with constituted authorities, and the highest tribunals in the land say "Stop," there is no other course for Latter-day Saints, in accordance with the revelations that God has given to us telling us to respect constituted authority, than to bow in submission thereto and leave the consequences with the Lord.[15]

The Manifesto thus strove to walk this difficult line–conceding sufficient to "constitutional authority" to prevent the Church’s destruction, maintaining the restrictions on plural marriage, and refraining from teaching the doctrine. Yet, significantly President Cannon says that the Saints "shall do the best we can" (emphasis added). That is, they will continue to practice their faith to the extent possible without threatening the Church’s existence. This would later include a limited continuation of plural marriage.

The Church leaders’ united understanding was that the Manifesto was a revelation. However, they did not understand it as universally forbidding all plural marriage at that time, though for the Church’s survival it was necessary that the government so interpret it.

The leaders and Saints would understand the meaning and application of the Manifesto differently in time. An altered understanding—via revelation—of a revelation is not unprecedented: Jesus commanded the apostles to "teach all nations," but the apostles continued to interpret this command in a more limited way until later revelation expanded the Christian gospel beyond those who had first embraced the rites of Judaism. A modern example involves the Word of Wisdom, which was not declared to be universally binding for more than a century, though the revelation in section 89 did not "change."[16]

It is estimated that fewer than two hundred plural marriages were sanctioned between 1890 and 1904.[17] These were often performed in areas outside the reach of U.S. law, such as on the seas or in Mexico.

Elder Dallin H. Oaks spoke at BYU about the difficulties of this period:

Some have suggested that it is morally permissible to lie to promote a good cause. For example, some Mormons have taught or implied that lying is okay if you are lying for the Lord… As far as concerns our own church and culture, the most common allegations of lying for the Lord swirl around the initiation, practice, and discontinuance of polygamy. The whole experience with polygamy was a fertile field for deception. It is not difficult for historians to quote LDS leaders and members in statements justifying, denying, or deploring deception in furtherance of this religious practice.

Elder Oaks then reaches the key point—there will be times when moral imperatives clash:

My heart breaks when I read of circumstances in which wives and children were presented with the terrible choice of lying about the whereabouts or existence of a husband or father on the one hand or telling the truth and seeing him go to jail on the other. These were not academic dilemmas. A father in jail took food off the table and fuel from the hearth. Those hard choices involved collisions between such fundamental emotions and needs as a commitment to the truth versus the need for loving companionship and relief from cold and hunger.

My heart also goes out to the Church leaders who were squeezed between their devotion to the truth and their devotion to their wives and children and to one another. To tell the truth could mean to betray a confidence or a cause or to send a brother to prison. There is no academic exercise in that choice!

It is also clear that polygamy did not end suddenly with the 1890 Manifesto. Polygamous relationships sealed before that revelation was announced continued for a generation. The performance of polygamous marriages also continued for a time outside the United States, where the application of the Manifesto was uncertain for a season. It appears that polygamous marriages also continued for about a decade in some other areas among leaders and members who took license from the ambiguities and pressures created by this high-level collision between resented laws and reverenced doctrines.

I do not know what to think of all of this, except I am glad I was not faced with the pressures those good people faced. My heart goes out to them for their bravery and their sacrifices, of which I am a direct beneficiary. I will not judge them. That judgment belongs to the Lord, who knows all of the circumstances and the hearts of the actors, a level of comprehension and wisdom not approached by even the most knowledgeable historians.[18]

Note: This article was adapted from a longer paper which examines these historical matters in much more detail. Interested readers are strongly encouraged to consult it for a much more thorough analysis of the basic concepts sketched in this wiki article. FAIR link PDF link

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now