FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

A FAIR Analysis of: MormonThink, a work by author: Anonymous

|

Book of Mormon Problems |

Jump to details:

This image below was in the Oct 2006 issue of the Ensign which shows both Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery at the same table with the plates in full view of both of them, which is not what is generally taught in the Church.

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

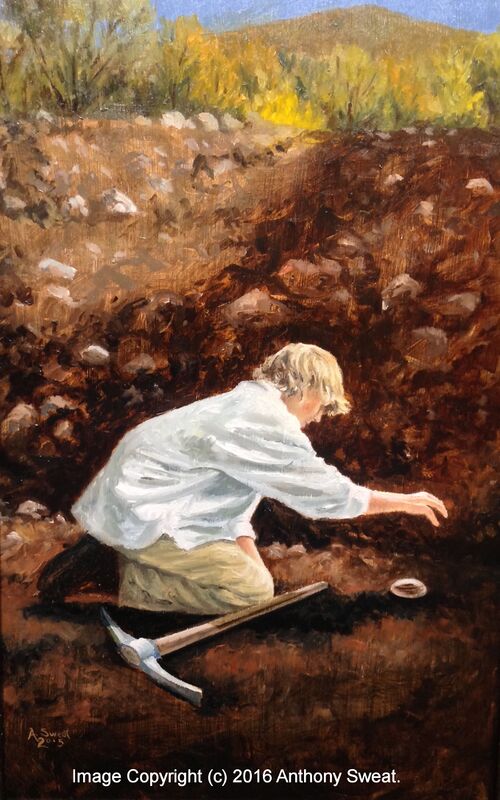

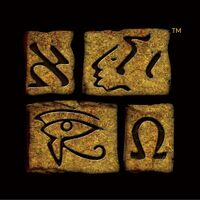

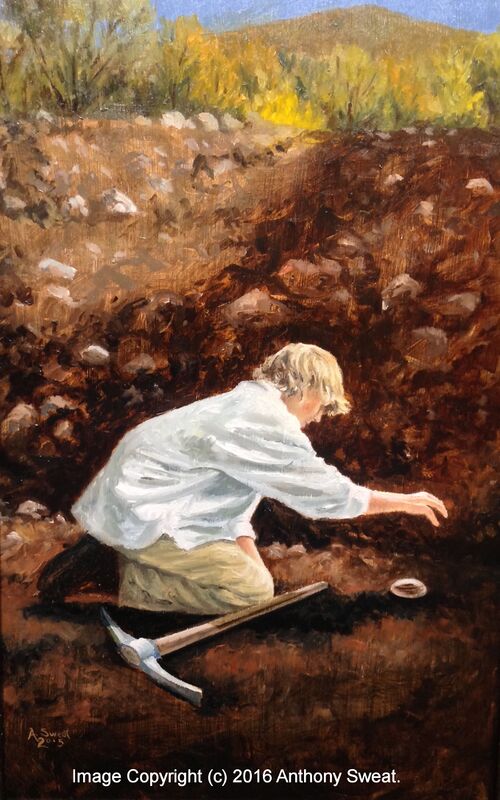

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

When Joseph was asked how exactly he translated the Book of Mormon, he never gave any details, he only said that he did it by the "gift and power of God." In a general conference of the Church in October 1831, in Orange, Ohio, Hyrum Smith asked his brother, Joseph, to give details of the BOM translation method. Joseph replied that "it was not expedient for him to tell more than had already been told about the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, and it was not well that any greater details be provided."

All that we know for certain is that Joseph translated the record "by the gift and power of God." (D&C 135:3) We are given some insight into the spiritual aspect of the translation process, when the Lord says to Oliver Cowdery:

"But, behold, I say unto you, that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you; therefore, you shall feel that it is right." (D&C 9:8)

Beyond this, the Church does not take any sort of official stand on the exact method by which the Book of Mormon translation occurred. Joseph Smith himself never recorded the precise physical details of the method of translation:

"Brother Joseph Smith, Jun., said that it was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon; and also said that it was not expedient for him to relate these things"[1]

It is important to remember that what we do know for certain is that the translation of the Book of Mormon was carried out "by the gift and power of God." These are the only words that Joseph Smith himself used to describe the translation process.

Gospel Topics on LDS.org:

[T]he scribes and others who observed the translation left numerous accounts that give insight into the process. Some accounts indicate that Joseph studied the characters on the plates. Most of the accounts speak of Joseph’s use of the Urim and Thummim (either the interpreters or the seer stone), and many accounts refer to his use of a single stone. According to these accounts, Joseph placed either the interpreters or the seer stone in a hat, pressed his face into the hat to block out extraneous light, and read aloud the English words that appeared on the instrument. The process as described brings to mind a passage from the Book of Mormon that speaks of God preparing “a stone, which shall shine forth in darkness unto light.”[2]

Russell M. Nelson:

The details of this miraculous method of translation are still not fully known. Yet we do have a few precious insights. David Whitmer wrote: “Joseph Smith would put the seer stone into a hat, and put his face in the hat, drawing it closely around his face to exclude the light; and in the darkness the spiritual light would shine. A piece of something resembling parchment would appear, and on that appeared the writing. One character at a time would appear, and under it was the interpretation in English. Brother Joseph would read off the English to Oliver Cowdery, who was his principal scribe, and when it was written down and repeated to Brother Joseph to see if it was correct, then it would disappear, and another character with the interpretation would appear. Thus the Book of Mormon was translated by the gift and power of God, and not by any power of man.” (David Whitmer, An Address to All Believers in Christ, Richmond, Mo.: n.p., 1887, p. 12.)[3]

Marcus B. Nash:

This was not a composition. This was dictated, word by word, as he looked into instruments the Lord prepared for him, using a hat to shield his eyes from extraneous light in order to plainly see the words as they appeared. Contrary to one who translates with the use of a dictionary, as it were, the translation was revelation flowing to him from heaven, and written by scribes (with the inevitable scrivener errors). [4]—(Click here to read more)

Roger Nicholson:

This essay seeks to examine the Book of Mormon translation method from the perspective of a regular, nonscholarly, believing member in the twenty-first century, by taking into account both what is learned in Church and what can be learned from historical records that are now easily available. What do we know? What should we know? How can a believing Latter-day Saint reconcile apparently conflicting accounts of the translation process? An examination of the historical sources is used to provide us with a fuller and more complete understanding of the complexity that exists in the early events of the Restoration. These accounts come from both believing and nonbelieving sources, and some skepticism ought to be employed in choosing to accept some of the interpretations offered by some of these sources as fact. However, an examination of these sources provides a larger picture, and the answers to these questions provide an enlightening look into Church history and the evolution of the translation story. This essay focuses primarily on the methods and instruments used in the translation process and how a faithful Latter-day Saint might view these as further evidence of truthfulness of the restored Gospel.[5]—(Click here to read more)

Brant Gardner:

A seer stone is a rock. We have seer stones. The church still has them, I’ve seen them. At one point in time I remember going on the temple square and going through the museum there and I saw one and I looked at it and I saw a rock. I didn’t see the translation, I didn’t see anything else I saw a rock. I can pretty much guarantee you that the vast majority of us as we would look at that rock would see, a rock. That does not mean that something isn’t working because they were looking at the rock and that’s what we have to look at. What we will be looking at is the idea that this whole concept of the seer stone working “It’s the seer that’s working,” and it’s stone that becomes the trigger that allows the seer to do what the seer does. So that’s kind of step one and we will talk about how that happens.[6]—(Click here to read more)

Most LDS are somewhat aware that Joseph Smith did some treasure seeking in his younger days. A following statement is sometimes quoted in church. This comes from Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, p.120: "Q: 'Was Joseph Smith not a money digger?' 'Yes, but it was not a very profitable job for him, as he only got fourteen dollars a month for it.'" This is usually the only thing said at church regarding his treasure-seeking past.

....

What is particularly noteworthy about this incident is the timing of the charges. These documents indicate that Joseph was involved in treasure seeking with a seer stone for profit after he received the First Vision but before he translated the Book of Mormon. How likely is it that the chosen prophet of the restoration would engage in such activities after conversing with Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ as well as the Angel Moroni? Would he really be doing such activities a year before he dug up the golden plates, after he had met with the angel Moroni for each of the prior three years?

Life and Character |

|

Youth |

|

Revelations and the Church |

|

Prophetic Statements |

|

Society |

|

Plural marriage (polygamy) |

|

Death |

Joseph Smith and some members of his family participated in "money digging" or looking for buried treasure as a youth. This was a common and accepted practice in their frontier culture, though the Smiths do not seem to have been involved to the extent claimed by some of the exaggerated attacks upon them by former neighbors.

In the young Joseph Smith's time and place, "money digging" was a popular, and sometimes respected activity. When Joseph was 16, the Palmyra Herald printed such remarks.

And, in 1825 the Wayne Sentinel in Palmyra reported that buried treasure had been found "by the help of a mineral stone, (which becomes transparent when placed in a hat and the light excluded by the face of him who looks into it)." [8]

Given the financial difficulties under which the Smith family labored, it would hardly be surprising that they might hope for such a reversal in their fortunes. Richard Bushman has compared the Smith's attitude toward treasure digging with a modern attitudes toward gambling, or buying a lottery ticket. Bushman points out that looking for treasure had little stigma attached to it among all classes in the 17th century, and continued to be respectable among the lower classes into the 18th and 19th.[9]

Despite the claims of critics, it is not clear that Joseph and his family saw their activities as "magical."

There are generally only a few questions that need to be addressed regarding Joseph's money-digging: his motives, his success, and the extent of his involvement. The first question is a question of what Joseph was doing while treasure seeking. Was he simply seeking to con people out of money in an easy way? The second question seems to be one of his abilities. How could he produce the Book of Mormon with something that didn't provide him any miraculous experience?

With regards to his success, it is, at the very least, plausible that he could see things in the stone that were invisible to the naked eye—just not treasure. There is, in fact, no recorded instance indicating that Joseph could see and locate treasure in the stones. There is, however, evidence that he could use the stone for more righteous purposes. A few pieces of historical testimony indicate this.

The next witness called was Deacon Isaiah Stowell. He confirmed all that is said above in relation to himself, and delineated many other circumstances not necessary to record. He swore that the prisoner possessed all the power he claimed, and declared he could see things fifty feet below the surface of the earth, as plain as the witness could see what was on the Justices’ table, and described very many circumstances to confirm his words. Justice Neeley soberly looked at the witness, and in a solemn, dignified voice said: "Deacon Stowell, do I understand you as swearing before God, under the solemn oath you have taken, that you believe the prisoner can see by the aid of the stone fifty feet below the surface of the earth; as plainly as you can see what is on my table?" "Do I believe it?" says Deacon Stowell; "do I believe it? No, it is not a matter of belief: I positively know it to be true."

Josiah Stowel [sic] sworn. Says that prisoner had been at his house something like five months. Had been employed by him to work on farm part of time; that he pretended to have skill of telling where hidden treasures in the earth were, by means of looking through a certain stone; that prisoner had looked for him sometimes, – once to tell him about money buried on Bend Mountain in Pennsylvania, once for gold on Monument Hill, and once for a salt-spring, – and that he positively knew that the prisoner could tell, and professed the art of seeing those valuable treasures through the medium of said stone: that he found the digging part at Bend and Monument Hill as prisoner represented it; that prisoner had looked through said stone for Deacon Attelon, for a mine – did not exactly find it, but got a piece of ore, which resembled gold, he thinks; that prisoner had told by means of this stone where a Mr. Bacon had buried money; that he and prisoner had been in search of it; that prisoner said that it was in a certain root of a stump five feet from surface of the earth, and with it would be found a tail-feather; that said Stowel and prisoner thereupon commenced digging, found a tail-feather, but money was gone; that he supposed that money moved down; that prisoner did not offer his services; that he never deceived him; that prisoner looked through stone, and described Josiah Stowel’s house and out-houses while at Palmyra, at Simpson Stowel’s, correctly; that he had told about a painted tree with a man’s hand painted upon it, by means of said stone; that he had been in company with prisoner digging for gold, and had the most implicit faith in prisoner’s skill.

There are a few other historical evidences that can be read to demonstrate Joseph's ability to see things in the stone.

"I…was picking my teeth with a pin while sitting on the bars. The pin caught in my teeth and dropped from my fingers into shavings and straw… We could not find it. I then took Joseph on surprise, and said to him–I said, ‘Take your stone.’ … He took it and placed it in his hat–the old white hat–and place his face in his hat. I watched him closely to see that he did not look to one side; he reached out his hand beyond me on the right, and moved a little stick and there I saw the pin, which he picked up and gave to me. I know he did not look out of the hat until after he had picked up the pin.[11]

In the same interview, Martin testified to Joseph's finding of the plates by the power of the seer stone:

In this stone he could see many things to my certain knowledge. It was by means of this stone he first discovered these plates.

"He [Joseph Smith] said he had a revelation from God that told him they [the Book of Mormon plates] were hid in a certain hill and he looked in his stone and saw them in the place of deposit.[12]

I have seen Joseph, however, place it to his eyes and instantly read signs 160 miles distant and tell exactly what was transpiring there. When I went to Harmony after him he told me the names of every hotel at which I had stopped on the road, read the signs, and described various scenes without having ever received any information from me.[13]

Willard Chase, one of the Smith's neighbors and a friend of Joseph's, found one of the stones. Chase let Joseph take the stone home, but as soon as it became known "what wonders he could discover by looking in it," Chase wanted it back. As late as 1830, Chase was still trying to get his hands on the stone. His younger brother Abel later told an interviewer that their sister Sally had a stone too. A nearby physician, John Stafford, reported that "the neighbors used to claim Sally Chase could look at a stone she had, and see money. Willard Chase used to dig when she found where the money was." After Joseph obtained the plates, Willard Chase led the group that searched the Smith's house, guided by Sally Chase and a "green glass, through which she could see many very wonderful things.[14]

Why would Willard and Sally chase after Joseph and his stone if he was utterly ineffective at seeing things in it?

What may be said about Joseph's abilities to see is that he could see things that allowed him to do good. He could not see that which he was not meant to see.

W.I. Appleby:

If Mr. Smith dug for money he considered it was a more honorable way of getting it than taking it from the widow and orphan; but few lazy, hireling priests of this age, would dig either for money or potatoes.[15]

Joseph's tongue-in-cheek response to one of a list of questions that were asked of him during a visit at Elder Cahoon's home:

Was not Joseph Smith a money digger? Yes, but it was never a very profitable job for him, as he only got fourteen dollars a month for it.[16]

It is currently[17] in debate what Joseph's motives were and how much he was involved.

Richard Bushman has written:

At present, a question remains about how involved Joseph Smith was in folk magic. Was he enthusiastically pursuing treasure seeking as a business in the 1820s, or was he a somewhat reluctant participant, egged on by his father?[18] Was his woldview fundamentally shaped by folk traditions? I think there is substantial evidence of his reluctance, and, in my opinion, the evidence for extensive involvement is tenuous. But this is a matter of degree. No one denies that magic was there, especially in the mid 1820s. Smith never repudiated folk traditions; he continued to use the seer stone until late in life and used it in the translation process.[19] It certainly had an influence on his outlook, but it was peripheral--not central. Biblical Christianity was the overwhelming influence in the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants. Folk magic was in the mix but was not the basic ingredient.[20][21]

What we do know is that after the Angel Moroni's appearance in 1823, Joseph began to turn away from treasure seeking. Again from Richard Bushman: